California's 2021–2025 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP)

A Five-Year Plan for Increasing Park Access, Community-Based Planning, and Health Partnerships Through Grants

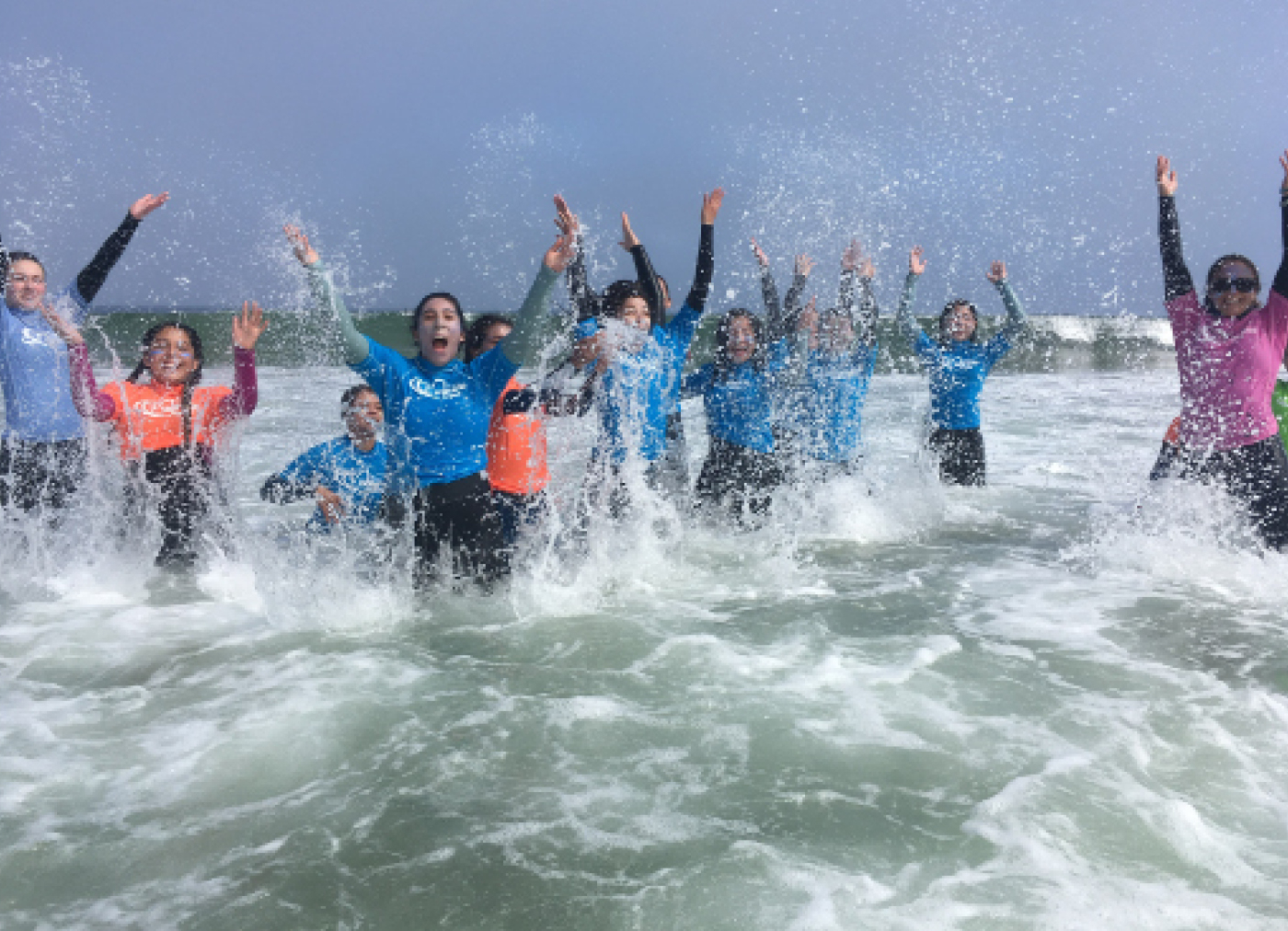

The SCORP was driven by 37 Public Focus Groups with over 500 community residents and university students statewide, who shared their ideas for making parks and recreation services a greater solution for health and wellness.

Welcome to California's 2021–2025 SCORP

This five-year plan for grants is produced by the California Department of Parks and Recreation's Community Engagement Division — Office of Grants and Local Services (OGALS).

Since 1965, over 7,580 parks throughout California have been created or improved with grants administered by OGALS. This includes over 1,000 parks in California funded through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Currently, more than 700 local agencies partner with OGALS in an effort to improve the health and wellness of California's 40 million residents by providing close to home park access.

OGALS GRANTS: parks.ca.gov/grants

Email: SCORP@parks.ca.gov

OGALS street address:

California Department of Parks and Recreation

Office of Grants and Local Services

1416 Ninth Street, Room 918

Sacramento, CA 95814

Table of Contents

Introduction

The California Department of Parks and Recreation

Park Partners Responding to Park Needs

Who Owns Park Land in California

California's Vision for Park Equity: Transforming Park Access Data and Technology

California Protected Area Database (CPAD)

Prioritizing Projects for Local Assistance Grant Programs such as the LWCF

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Using Geospatial Technology to Identify Park Access Priorities

Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning Methods

Three-Step Public Engagement Model

Historical Significance of Statewide Park Program Community-Based Planning

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning

37 Focus Groups Statewide: Methods and Findings

Seven SCORP Advisory Council Focus Groups

- Methods

- Findings associated with the questions below:

- The California Department of Parks and Recreation understands that there may be health and safety challenges within your community. What types of park projects or programs do you think can help, and why?

- Has a park or recreation program changed your life? How?

- Is there anything else you want to tell state leaders about parks and recreation in your community?

- SCORP Public Focus Group Locations

- 2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan From Focus Group Findings

Health Partnerships

Grant Incentives for Partnerships

Connecting Health and Park Agencies

California's Health in All Policies (HiAP)

Active Parks, Healthy People Pilot Program

Examples of Health and Park Agency Partnerships

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Health Partnerships

State Agencies, Wetlands, and LWCF Grant Projects

- California Department of Parks and Recreation — State Parks

- Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Wildlife Conservation Board

- Department of Water Resources

- State Coastal Conservancy

- LWCF Process for annual State Agency allocations

Protection of Natural Resources

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Wetlands

Action Plan Summary for 2021–2025

SCORP is a five-year plan that establishes grant priorities to address unmet needs for public outdoor recreation land throughout California. By creating the five-year SCORP action plan for grant-making priorities, California maintains eligibility for federal Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) grants.

Executive Summary

SCORP is a product of the California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) — Community Engagement Division (CED) — Office of Grants and Local Services (OGALS). OGALS administers LWCF on behalf of California. The LWCF Act of 1965 intends to "strengthen the health and vitality of citizens" by creating and preserving outdoor recreation land in perpetuity. Since 1965, nearly 7,600 parks in California have been created or improved with federal and state grants administered by OGALS, including over 1,000 parks funded by the LWCF. Currently, more than 700 local agencies partner with OGALS to create and improve close-to-home park access for the health and wellness of California's 40 million residents.

Grants: Five-Year Action Plan

Local agency grantees* will create, expand, or improve park access within a half mile of underserved communities. For park design, community-based planning methods give local agencies flexibility to propose features authentic to each community's unique recreation needs. Projects will increase athletics, art, and nature-based recreation opportunities for the health and wellness of all age groups.

* Local agencies propose projects to OGALS through a statewide competitive process.

State agency grantees* will enhance the resiliency of California's natural resources including but not limited to wetlands, forests, deserts, watersheds, coastal areas and other open space through acquisition or development projects to improve public outdoor recreation access and advance solutions to confront climate change. Per Executive Order N-82-20, California has pledged to conserve 30 percent of land and coastal waters by the year 2030. Each eligible state agency has its own action plan priorities in this SCORP.

* California's Public Resource Code §5099.12 makes a percentage of annual LWCF funds available to State Parks, Department of Water Resources, California Wildlife Conservation Board, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the California Coastal Conservancy.

All local and state agency lands funded by LWCF are protected in perpetuity for the benefit of future generations through Section 6(f)(3) of the LWCF Act.

From 2016 to 2020, park access, community-based planning, and health partnerships were the overarching themes associated with park development grant programs awarded in California. These themes emerged during four years of statewide discussions:

2016–17: Thirty-seven focus groups, which included more than 500 public participants, park and recreation providers, university professors, and health sector professionals, supported a SCORP emphasis on increasing access to parks and recreation services for community health and wellness.

2018: Californians passed the Drought, Water, Parks, Climate, Coastal Protection, and Outdoor Access for All Act of 2018 (Proposition 68). This action strengthened the nexus between park access and improving the physical and emotional health of communities, and sought to address rising health care costs and obesity-related illnesses.

2018 to 2020: Over 500 local agencies discussed park access, community-based planning, and health partnerships in over 20 hearings and workshops for the Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP). These efforts resulted in $2.3 billion in competitive park projects requests during the most recent 2019–20 cycle.

Products of California's 2021–2025 SCORP

- This Summary Report: California's 2021–2025 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan — A Five Year Plan for Increasing Park Access, Community-Based Planning, and Health Partnerships Through Grants

- Report on California's Vision for Park Equity 2000–2020: Transforming Park Access Data and Technology

- Report on Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning — Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program

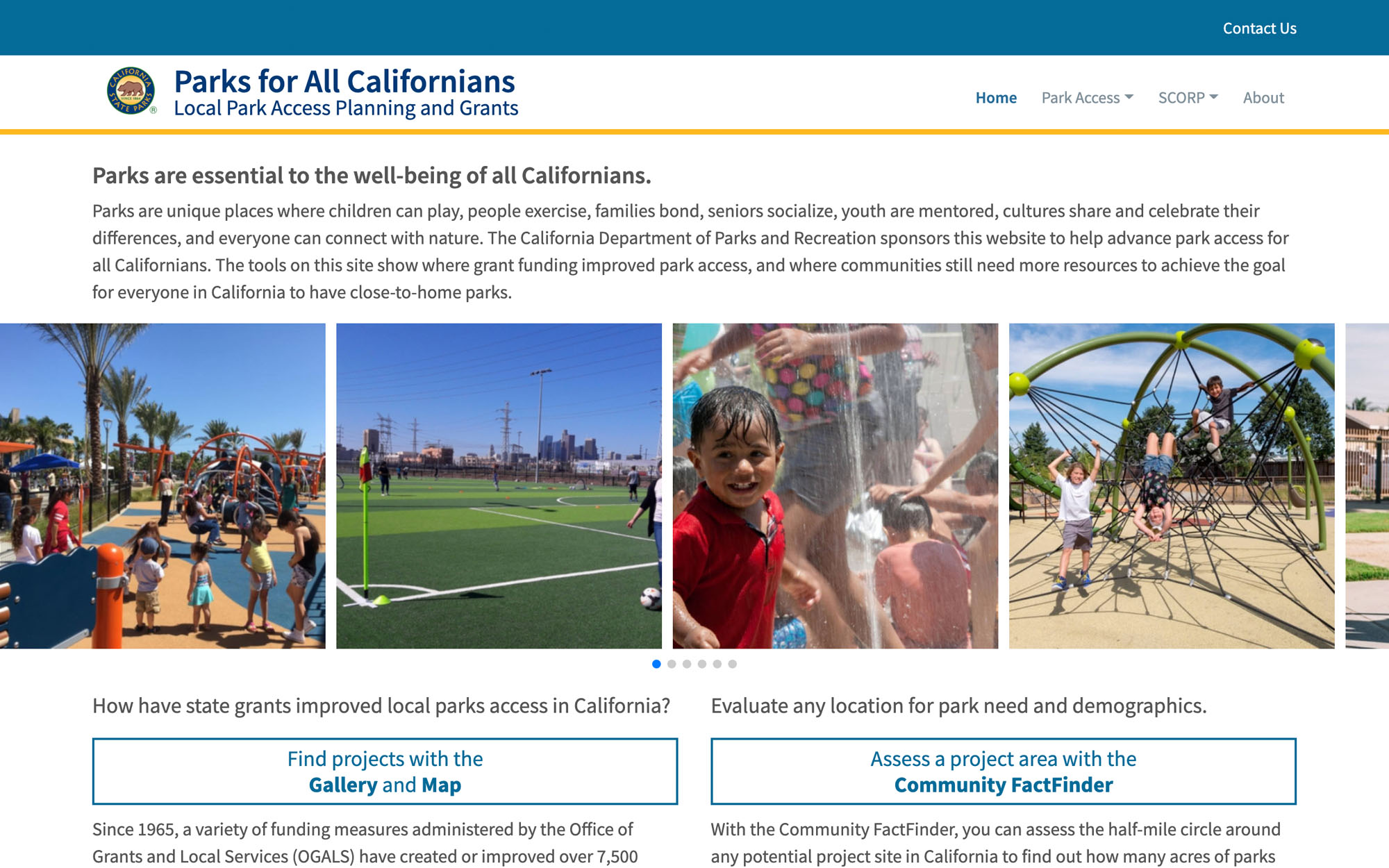

"Parks for All Californians" website at ParksforCalifornia.org

- Park Access Tool

- Community Fact Finder Tool

- Grant Allocations

- Explanation of GIS tool data methods

California's last SCORP was updated in 2015. The 2021–2025 SCORP improves upon the previous one and summarizes recent key finding from focus groups and continues the vision for local assistance grant programs including the use of LWCF allocations to California. For further guidance on how to submit LWCF funding applications, including Project Selection Criteria, go to parks.ca.gov/grants_lwcf .

The California Department of Parks and Recreation

California has benefited greatly from both public and private agencies that have made public outdoor spaces a priority. The California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) serves an important public agency role that administers the following:

State Park System — Protects landscapes where nature is primary and facilities complement natural and cultural/historic values. With 280 state park units, over 340 miles of coastline, 991 miles of lake and river frontage, more than 14,000 campsites, and more than 5,000 miles of motorized and non-motorized trails, DPR contains the largest and most diverse recreational, natural, and cultural heritage holdings of any state agency in the nation.

Develop and maintain the SCORP — Develops analysis, goals, tracking systems and range of partnerships to achieve a five year action plan, which includes facilitating discussion and outreach regarding the action plan's goals and programs.

Fund Local Needs — Develops and administers local assistance grant programs from bond acts or federally or state funded annual programs through OGALS, Division of Boating and Waterways and Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation, and Office of Historic Preservation. Since 2000, DPR administered over $3 billion in grants.

Facilitates planning, technical assistance, and partnerships — between the health, educational, environmental sectors and local park agencies to build healthier communities through new parks and programs.

Park Partners Responding to Park Needs

California's 155-year parks legacy has been created through the actions of nearly 1,000 public agencies and nonprofits. These park partners reflect the diversity of California's park needs:

Local agencies — provide close-to-home active recreation facilities, such as sports courts/fields, community centers, and neighborhood parks (plus some broader open space roles) — includes city, county, and special district/recreation districts.

Regional agencies — conserve larger landscapes/habitats and provide hiking, camping, etc. in large open spaces — includes regional park and open space districts and joint powers authorities.

State agencies — preserve significant natural and cultural areas. Facility development in state parks, by law, must complement parks' natural/cultural integrity. The Department of Fish and Wildlife, 10 state conservancies, CAL FIRE, Department of Water Resources, The State Lands Commission, and state universities, all protect and preserve fish and wildlife resources, forests, and broad areas of public land.

Federal agencies — primarily conserve iconic natural and cultural resources and sites, rather than providing developed recreation. This is accomplished through the National Parks System, the National Wildlife Refuge System, the vast National Forests, deserts and other public lands overseen by the Bureau of Land Management and lakes and reservoirs from the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation.

Non profits / Other — land trusts and community organizations often own publicly accessible preserves and neighborhood parks or partner with public agencies to offer programs and services. The health sector, foundations, and businesses contribute funding and the people of California volunteer time and resources to support parks.

By number, parks are mostly owned by city, special district and county agencies

| Type of Owner | Acres |

|---|---|

| City | 9,000 |

| County | 1,200 |

| Special District | 1,700 |

| State | 631 |

| Federal | 500 |

| Non Profit, other | 450 |

By acres, parks and open space are mainly owned by federal and state agencies

| Type of Owner | Acres |

|---|---|

| City | 316,000 |

| County | 238,000 |

| Special District | 445,000 |

| State | 1,990,000 |

| Federal | 43,700,000 |

| Non Profit, other | 210,000 |

To learn more about California's park inventory, see an additional SCORP report named California's Vision for Park Equity 2000–2020: Transforming Park Access Data and Technology at parksforcalifornia.org

Agencies and advocates across California are increasingly committed to ensuring that every Californian has equitable access to parks. Over the past decade, grant programs have incorporated the use of online Geospatial Analysis tools to help identify and analyze which communities lack adequate access to parks.

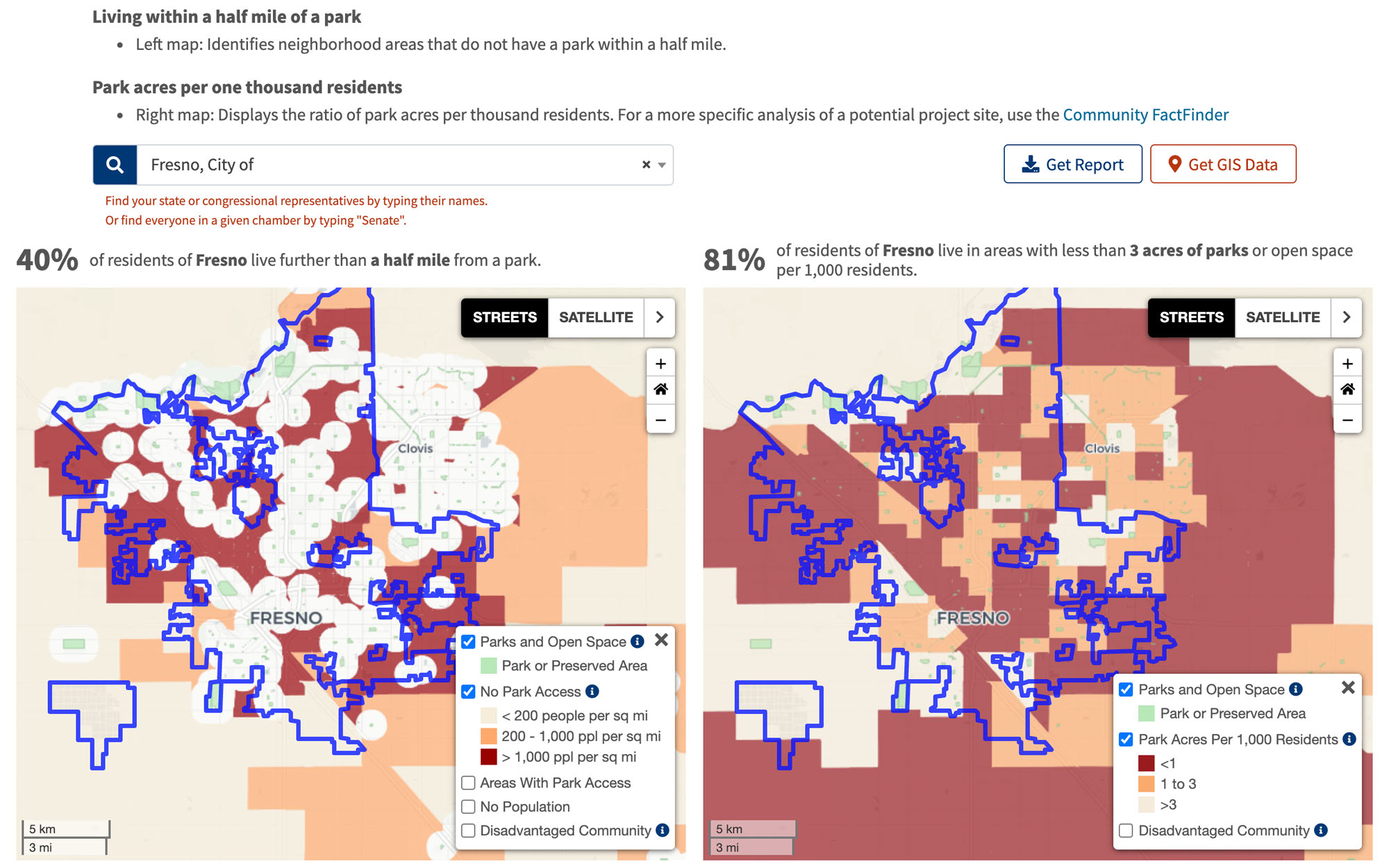

The 2021–2025 SCORP continues the analysis of park access in California using the following inventory and tools:

California Protected Areas Database (CPAD)

Provides an inventory of over 14,000 public parks and open space areas statewide. calands.org

Park Access Tool

Provides a broad analysis at larger geographic scales to calculate 1) the ratio of park acres per thousand people, and, 2) the percentage of people who live within a half-mile of a park. In 2015, when OGALS first launched this tool for the 2015–2020 SCORP, findings indicated that:

- Over 60% of Californians live in Census Tracts with less than 3 acres of parkland per 1,000 residents.

- Nearly 9 million people, 24% of Californians, have no park within a half mile of their homes.

In the update for the 2021–2025 SCORP, OGALS found that:

- Over 61% of Californians live in Census Tracts with less than 3 acres of parkland per 1,000 residents.

- Nearly 8 million people, 21% of Californians, have no park within a half mile of their homes.

To better understand how these communities that lack park access fit within the larger picture in California, statistics are available for cities, counties, regions, and legislative districts.

parksforcalifornia.org/parkaccess

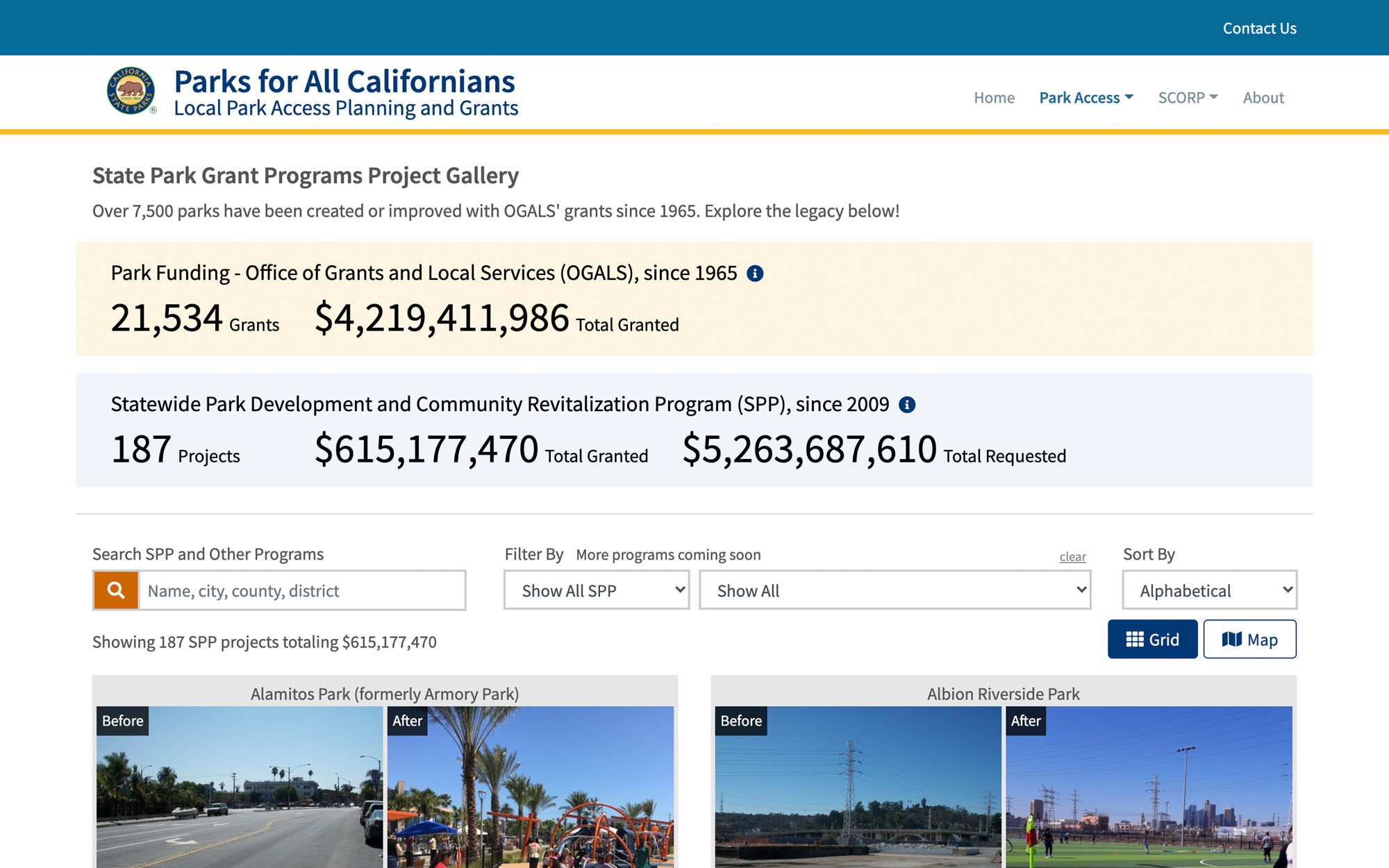

Park Access Progress: 1 million more Californians have park access located within a half mile radius of their home in 2020 findings compared to 2015. This progress has been partially reached through the Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program, which created more than 100 parks within a half mile radius of more than 1 million Californians through two rounds of Proposition 84 funding.

Park Access Investments by the Numbers

The following provides a 10-year review of statewide park investments.

Proposition 84 SPP Rounds One and Two

- Between two competitive rounds in 2009/10, 125 SPP parks were funded through $368 million, with an average grant amount of $2.7 million.

- Approximately 1 million Californians live within a half-mile of the 125 grant funded sites.

- These numbers show that in 2009/10, an investment of $368 million created new park access for every 1 million Californians.

- Considering a 2010 investment for 30 years of public use through 2040, providing new park access within a half mile of 1 million Californians calculated to $11 per person per year, or 94 cents per month, or 3 cents per day.

Proposition 68 SPP Round Three

- In 2019/20, 62 parks were funded through $255 million, with an average grant amount of $4.1 million.

- Approximately 500,000 Californians live within a half-mile of the 62 grant funded sites.

- These numbers show that in the 2019/20 SPP Round Three, an investment of $255 million created new park access for nearly 500,000 Californians within a half mile radius of 62 projects.

- Considering an investment for 30 years of public use through 2050, providing new park access within a half mile of every 500,000 Californians now calculates to $17 per person per year, or $1.41 per month, or 5 cents per day.

- The upcoming Round Four will make an additional $395.3 million available. Competitive project applications are due in March 2021. This final round of Proposition 68 SPP may provide park access for an additional 500,000 or more Californians within a half mile of their neighborhoods.

Conclusion

Based on these patterns between three SPP rounds of funding for community park development, an average of approximately 60 park projects per round are creating new park access for approximately 500,000 Californians within a half mile radius per round. Land acquisition and construction prices have increased by approximately $1,500,000 per project site over the past decade from 2010 to 2020. Based on current projections, for each $600 million investment, an additional 1 million Californians will have new or expanded park access within a half mile of their neighborhoods.

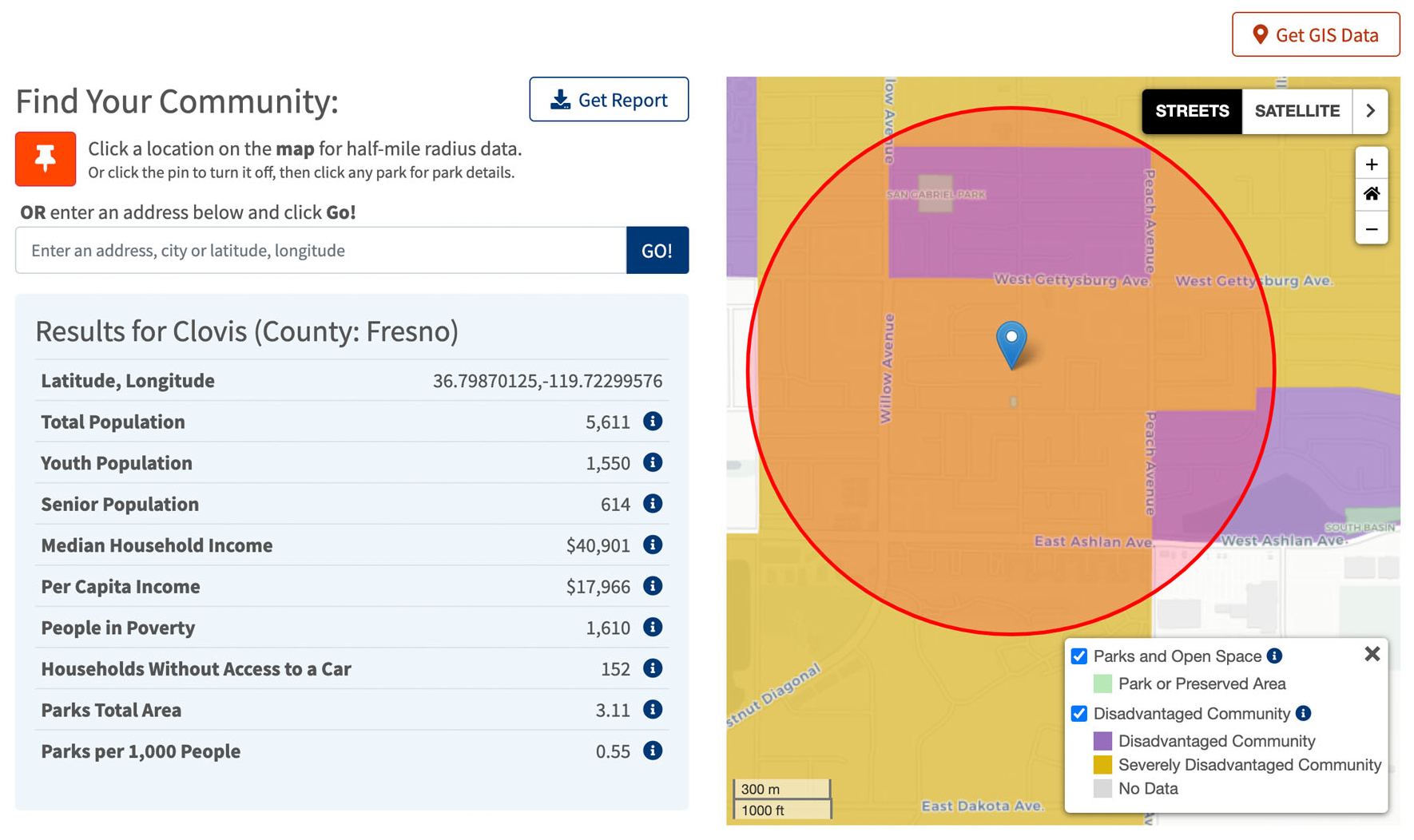

This picture of the larger landscape provided by the Park Access Tool is important, but the site-specific Community FactFinder is essential for making the most informed decisions about project areas.

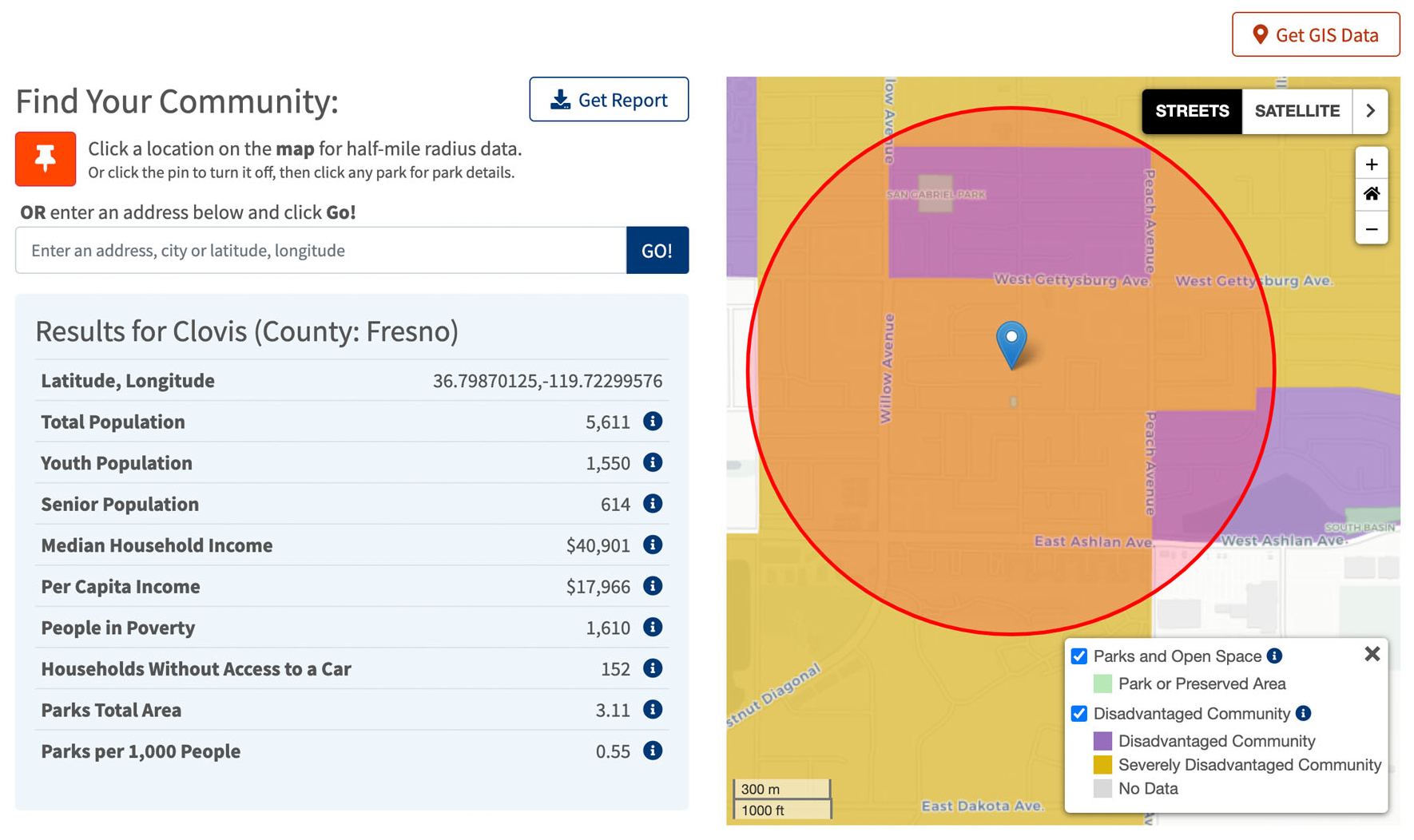

Community FactFinder

The Community FactFinder provides DPR and the public site-specific data within the half-mile radius of any park project area. The data helps users evaluate a specific area where a grant applicant proposes to build a project, in comparison to all competing statewide applications. Additionally, the Community FactFinder helps steer local park planners and grant applicants to locate projects in underserved communities.

Prioritizing Projects for Local Assistance Grant Programs such as the LWCF

Considering California's almost 40 million residents and the complexity and high need for parks throughout urban, suburban, and rural communities, local assistance grant programs, including LWCF, do not "pre-select" a few communities to receive grant funding. Instead, California's LWCF and the Statewide Park Program provide these tools to applicants to help them identify high priority areas in their jurisdictions. Once applications are submitted to CED/OGALS, the competitive applications go through a statewide analysis using the same tools. While the use and ranking of consistent data to measure park deficiency and poverty is valuable to help prioritize projects, any competitive grant review process should also include analysis and professional judgment of other factors including the project's need and benefits.

For more information about the evolution of these tools, challenges, and lessons learned, the 2021–2025 SCORP includes an additional report named California's Vision for Park Equity 2000–2020: Transforming Park Access Data and Technology. This report is available at ParksforCalifornia.org

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Using Geospatial Technology to Identify Park Access Priorities

- Continue updating the California Protected Area Database (CPAD) as a vital inventory and resource for assessing park acreage statewide.

- Continue using the Community FactFinder for site-specific data analysis of proposed projects.

- In 2025, release the next version of the Park Access Tool for the 2025–2030 SCORP, building upon the 2015 and 2020 editions.

- Monitor data and technology for improvements, especially in these forms:

- Network analysis for walking routes specifically, to increase the accuracy of the 10-minute walk shed of each park, excluding areas that are impassable due to freeways, railroads, or other areas impassable to pedestrians.

- Accessible mapping technologies for low- and no-vision users.

- Participatory mapping technologies that enable community members to provide spatially specific comments, images, and stories about park design and park access in their neighborhoods.

Encouraging community-based planning in grant programs is founded on this basic question: For community parks, should California prioritize one type of recreation facility over another, based on national, state, or regional surveys?

Historically, in competitive programs, grant writers and even grant guidelines cited national, state, or regional surveys to determine what types of recreation facilities should be included in a community park. For example, the results of regional or statewide surveys were used to prioritize which type of facility ranked higher in California's competitive LWCF applications. A picnic area ranked higher than a playground, a baseball field ranked higher than a soccer field, and a tennis court higher than a basketball court.

However, during LWCF application workshops, local government applicants frequently reported that their community's needs were different from the statewide or regional survey results. National, state, or regional surveys may not capture the recreation feature priorities of cities, and even more specifically, of neighborhoods within different areas of the same cities. Each community has unique unmet recreation needs for park access and infrastructure.

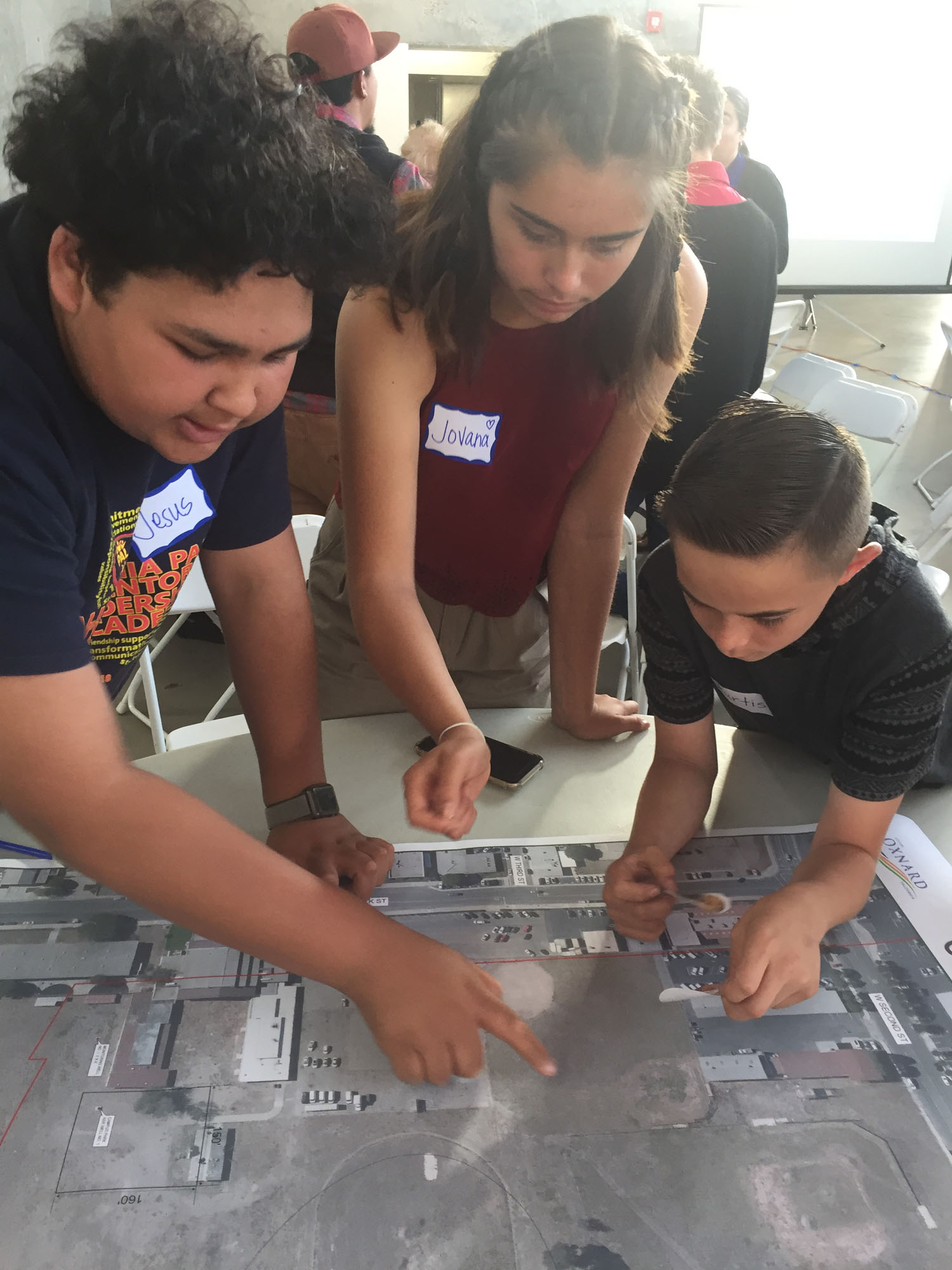

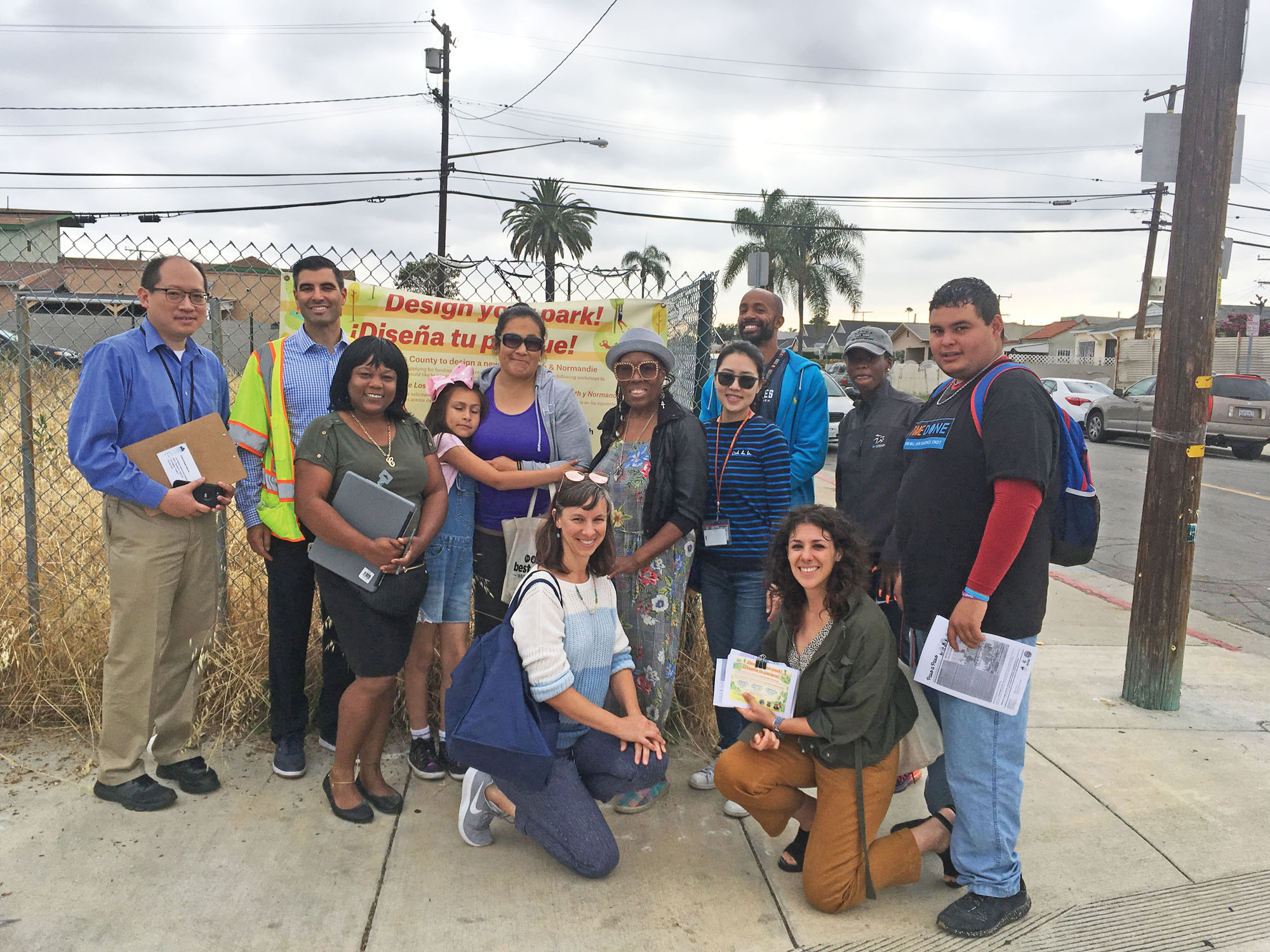

For these reasons, California's SCORP encourages flexibility in park design responsive to each community's unique recreation needs. SCORP provides methods learned from hundreds of local park agencies and nonprofit organizations, using a three-step public engagement model for designing community parks. The three-step model was developed and tested through California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP).

Three-Step Public Engagement Model

SPP's grant guidelines, written with feedback from hundreds of local park agencies and nonprofit organizations, led to the development of a three-step public engagement model for designing community parks.

The steps include:

- Scheduling five accessible park design meetings at or near the project site, at different times including weekends or evenings.

- Inviting and involving youth, seniors, and families living in the project area to engage in an active planning process.

- Conducting interactive and dynamic meetings to achieve the following park design goals:

- Selecting and designing recreation features.

- Locating the selected recreation features within the park.

- Identifying safe public use and park beautification ideas.

This process encourages meaningful engagement between neighbors, local government, and organizations. These steps lead to authentic park designs representing each community's unique recreation needs and values.

To learn more, see Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning — Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program.

Historical Significance of SPP Community-Based Planning

California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP) is the country's largest state-administered grant program for community parks. This historically significant grant program has provided more than $1 billion in grant funding through Proposition 84 in 2006 and Proposition 68 in 2018.

SPP has funded the creation of 130 new parks and 60 park expansions or renovations throughout California. With $5.2 billion in grant requests received for $623 million in available funding between three rounds, thousands of residents became civically engaged in their local park designs.

SPP Rounds One and Two: Proposition 84 (2006 Bond Act) made $368 million available for SPP grants. Nine hundred project proposals were received requesting $2.9 billion.

SPP Round Three: Proposition 68 (2018 Bond Act) made $650 million available for SPP grants. Round three made available $254.9 million. A total of 478 project proposals requesting $2.3 billion were received on Aug. 5, 2019.

SPP Round Four: The remaining $395 million of Proposition 68 SPP will be awarded through a Round Four competitive process in 2021.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, new methods for remote park design meetings and tools are currently being tested in preparation for a March 2021 SPP Round 4 application deadline. Methods that are proven to be successful may be featured in California's 2025–2030 SCORP if remote web-based meetings are necessary. To inform future planning efforts over the next five years, DPR's Community Engagement Division will continue to share successful methods learned through this SPP model.

Below are two examples showing how SPP projects transform communities. To see more statewide "Before and After" photos, visit ParksforCalifornia.org

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning

CED/OGALS will be responsible for the following 2021–2025 SCORP actions for local assistance grants:

- Allow grant applicants to design parks that are authentic to each community's unique recreation needs. Competitive grant criteria will not use a national, state, or regional survey to pre-determine what type of recreation feature is the highest priority for a community.

- Consider how public engagement for park design may occur under future COVID-19 health guidelines. This consideration includes identifying how authentic community-based planning may involve the elderly and other Californians who may lack high-speed internet connection, computers, and cell phones, share successful solutions for community engagement that may be learned through Round 4 of the SPP.

- Provide the report named Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning — Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program as technical assistance examples for grant projects, including:

- The upcoming competitive round(s) of SPP.

- $23 million Proposition 68 Regional Park Program.

- $23 million Proposition 68 Rural Recreation and Tourism Program.

- LWCF Program.

- Non-motorized Recreational Trail Program.

- Share the report named Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning — Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program with:

- Other states, through the City Parks Alliance, National Recreation and Parks Association (NRPA), American Planning Association, National Association of State Outdoor Recreation Liaison Officers (NASORLO), Society of Outdoor Recreation Planners (SORP), American Society of Landscape Architects (ASPA), and other national associations.

- California's Park and Recreation Society (CPRS), California Association of Recreation and Park Districts (CARPD), and California's Health in All Policies (HiAP).

- California State University Recreation departments to inspire future planners and policy leaders.

- 700 local agencies and nonprofit organizations throughout California.

"India Basin (900 Innes Boatyard) is the most ambitious park project in a generation, and we wanted to design something not just for the surrounding community, but with them. It's going to be an anchor of health, safety, economic development, culture and environmental justice in the neighborhood. We are so proud to be working alongside them to make it happen."

Phil Ginsburg | General Manager, San Francisco Recreation and Parks

"As Recreation Professionals, we often have a general idea as to what our community wants and needs in our neighborhood parks; however, community-based planning allows for a much deeper connection to the neighborhood and ultimately leads to a much better project with much more community pride.

It brought the whole neighborhood closer together."

Tina Cherry | Community Services Director, City of Monrovia, Lucinda Garcia Park

"Community-based planning allows the opportunity to give community members a voice and creates relationships that bring insight and perspectives that are normally ignored. Regardless if the grant is awarded, it is a worthwhile experience in future revitalization opportunities."

Francesca Sciamanna | Community Services, City of Bell

"Just planning the park has brought the community together. Boorman Park is the community's baby. This project reflects in-depth community planning to represent what we really want and need in a park. This grant gives us the inspiration to keep active in the community. We are so proud of this effort. The community has finally been heard and our kids will benefit for years!"

Maria Isabel Barrera | West County Regional Group member and resident of the Boorman Park area.

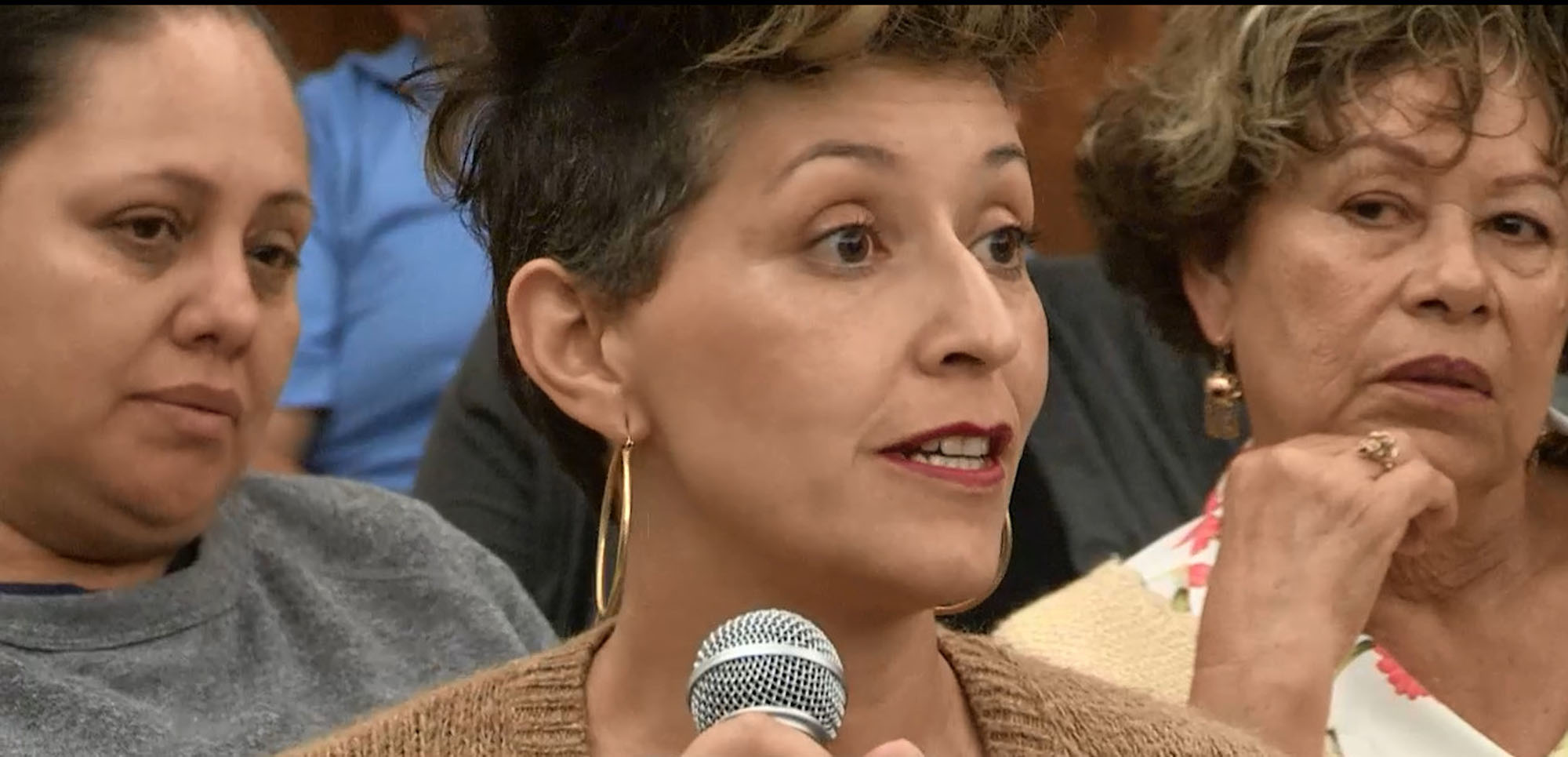

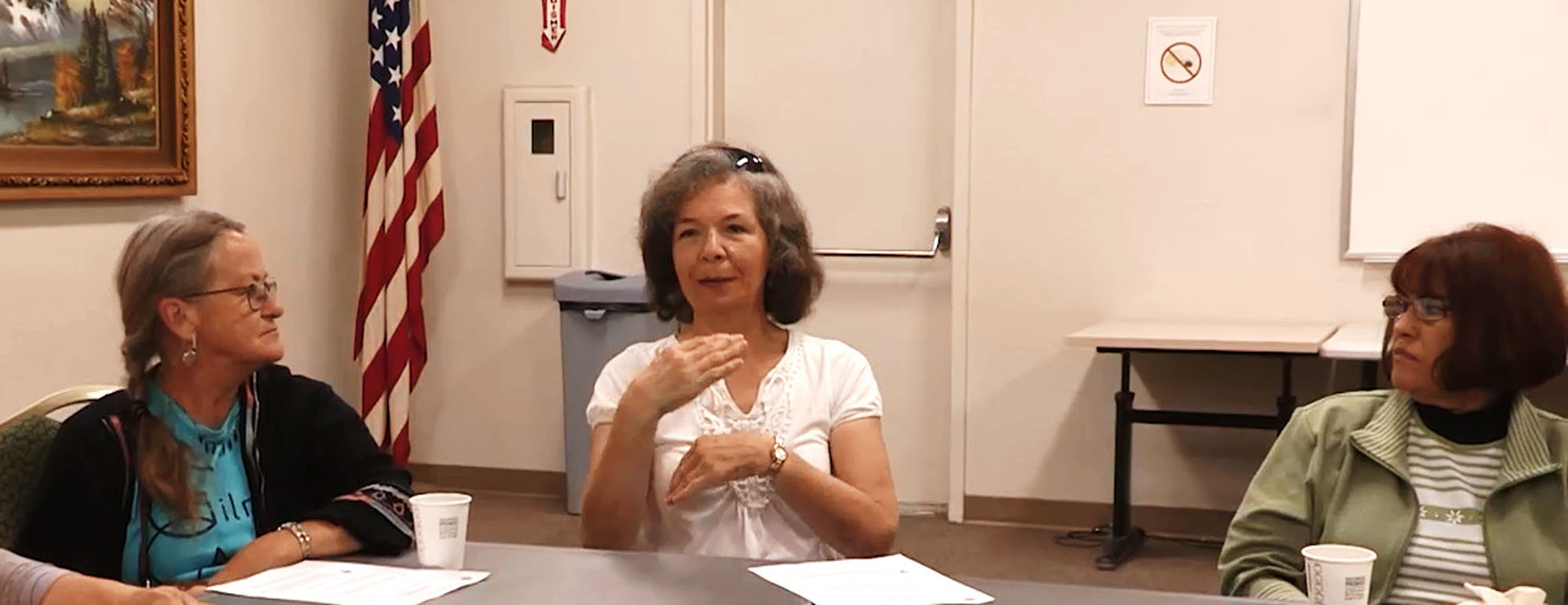

Thirty-seven focus groups, which comprised of five hundred Californians, shared their vision for parks and recreation and California's 2021–2025 SCORP.

The following examples explain how local community members, college students, regional and state government officials, foundations, health, and community-based organizations participated.

Seven SCORP Advisory Council Focus Groups

To help shape the vision for California's 2021–2025 SCORP, the Community Engagement Division first formed an Advisory Council to listen to issues of statewide significance. The focus groups took place in Anaheim, Fresno, Oakland, Redding, San Diego, Santa Clarita, and West Sacramento from September through October 2016. One hundred leaders were brought together to these locations.

Method

The Advisory Council members were selected to represent diverse perspectives including academia, the health sector, local and state government, foundations, and community-based organizations.

- Each focus group was three hours long.

- Members discussed challenges and opportunities facing parks and recreation in their region.

- Discussions were facilitated to encourage a free flowing, high-level exchange of ideas under the broad topic of what challenges and opportunities face parks and recreation in their region.

- By discussing challenges and opportunities in each region, consistent priorities were identified between all regions.

RAND, Santa Monica

CSU San Francisco

CSU Chico

California State Parks

CSU Fresno

City of Fresno Parks Director, Ret.

The following describes key findings between the seven statewide Advisory Council Focus Groups:

Findings

The most surprising discovery from the 2016 discussions was sensing the park and recreation profession was suffering from an identity problem.

In summary:

- Marketing park and recreation services to the general public requires a different approach than trying to gain budget support from governing bodies. Local park agencies typically market their services as being "fun" to encourage the public to use local parks and recreation programs. However, city council, or county board of supervisors generally do not prioritize "having fun" over public health and safety such as police and fire. Local directors often feel that they are competing with other public service agencies for budget support.

- Local park agencies were being required to become revenue generators, renamed or merged into broader non-park agencies such as "Community Services" or "Public Works."

"Pay to Play" and "Revenue Generation" Trend

An intriguing discussion arose about how marketing the "fun" of parks and recreation often works well to attract the public, but may affect the image and perception of these services as essential. Local park agency directors candidly expressed, "I feel we are not taken seriously" and "we need to do a better job telling our story."

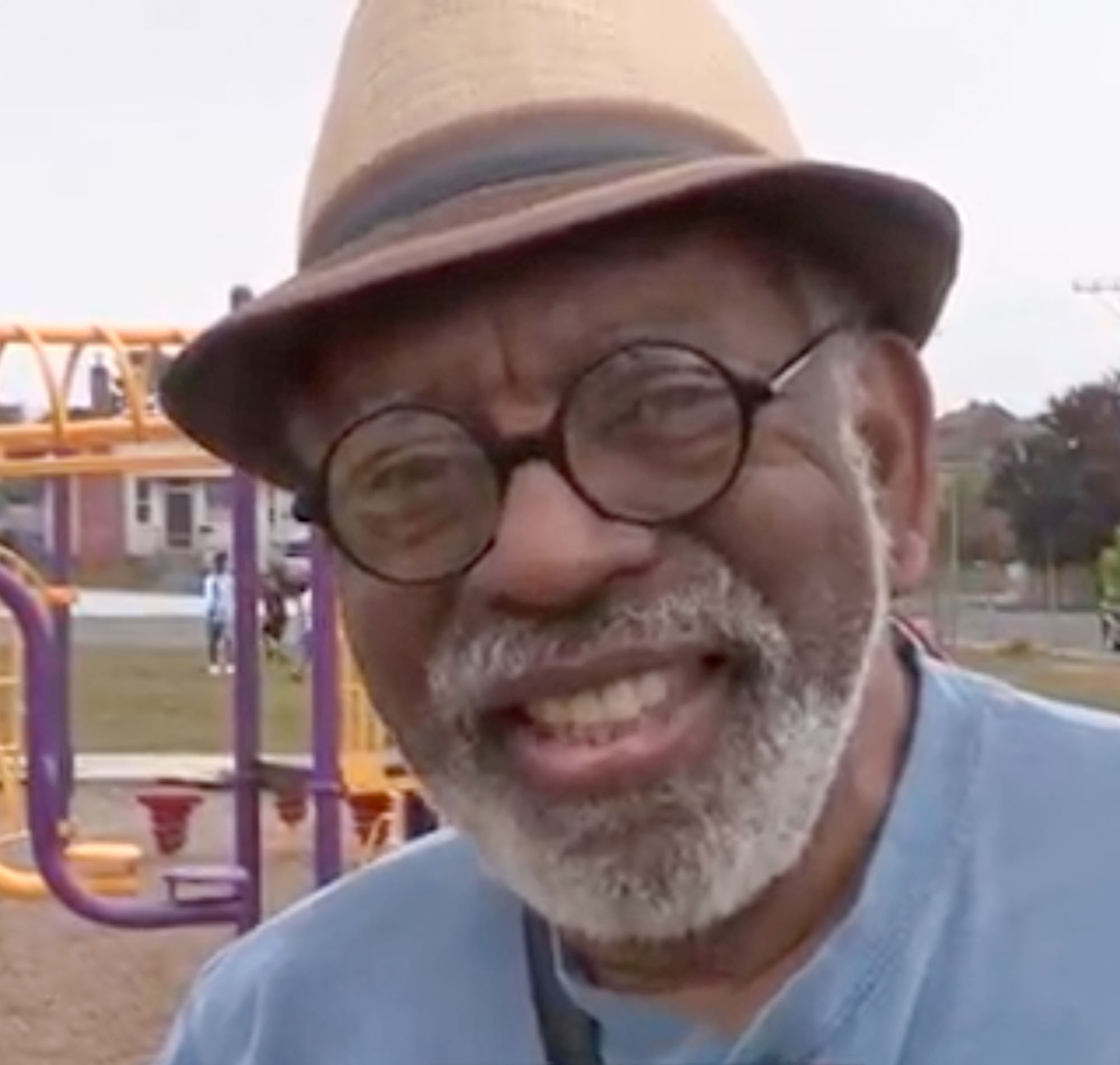

The focus groups touched on our country's work-driven culture that generally does not recognize "fun" or "play" as an essential activity. The work-driven cultural norm appears to clash with the park and recreation sector's belief that play and fun are critical for personal wellness and a community's social health. "Play is not valued as a priority in our society but is fundamental to the development of people." Sedrick Mitchell, Deputy Director, Community Engagement Division, DPR.

Local park agency directors reported that they are required to function under a business model in order to support operations due to budget constraints. "This shifts our service focus and mission" said a local agency director. The business model emphasis may cater to those who can afford to pay, while widening the "equity" service gap for economically disadvantaged members of the public.

Participants pointed out that trying to explain the benefits of parks and recreation has been a long-standing effort within the profession. Advocacy must go beyond saying how great current park and recreation services are, to include a vision for greater investments in parks and recreation to achieve new health benefits. Expanding services to confront health challenges may require a philosophical change in the profession. Some directors spoke passionately about being on the "front line" and "in the trenches." Many park agencies are providing social services such as meals, counseling services, health screenings, clothing distribution, after school tutoring, providing a positive alternative to gangs, life skills classes, etc. Therapeutic recreational programs for war veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and employment development programs were also cited as examples of park agency functions.

People Who Are Homeless and Local Parks

Local park directors explained that there is an increasing amount of people who appear to the general public as being homeless in local parks. The directors had different views of solutions, from collaborating with other local service providers and faith-based organizations to serve people who are homeless, or to design parks that attract more public use. Various ideas were shared to make parks less likely to be sites for encampments, such as designing parks for more active use (skate parks, dog parks, sports courts, running tracks, outdoor gym equipment, etc.) or scheduling supervised recreational events and activities (sports leagues, exercise groups, music, dance, art, movie nights, community events, etc.).

The Words "Recreation" and "Parks" have Different Meanings to Different Audiences

The Advisory Council also pointed out a basic, fundamental issue often not recognized by park professionals: the word "recreation" and "park" is not universally understood for these reasons:

- Some people think the word "recreation" means how people generally spend free time such as watching television, shopping, playing video games, tourism, etc.

- The word "recreation" is also a complex public service to define. Recreation may mean team or individual sports and leagues to some, or viewing wildlife in remote natural areas to others. From arts and crafts, music, dance, theater, to exercise groups, walking, biking, hiking, picnicking/barbeques, camping, fishing or hunting, paddling, boating, horse-back riding or riding off-highway motorized vehicles, and visiting historic sites, "recreation in parks" means a wide range of possibilities.

- The word "park" may also need to be more clearly defined in context depending on the intended audience or purpose because it may not evoke a consistent image. Neighborhood pocket parks, community parks, city, county, regional, state, and national parks all meet diverse needs and interests. In addition, a public beach or "open space" preserve with a trail is often not envisioned or labeled as a "park," but provides public recreational opportunities comparable to many regional, state, or national parks.

- Therefore, a specific type of "recreation" or "park" may need to be clear depending on the communication goal and intended audience.

Advisory Council members mentioned that distant parks are more difficult to access on a daily basis due to economic, daily schedule, and physical barriers. Some Californians cannot afford to drive to distant parks or do not have time to visit travel destinations due to busy schedules.

Using Neighborhood Parks as Greater Solutions for Health Issues

Dr. Deborah Cohen, formerly with RAND Corporation, commented that "many existing parks are untapped solutions for health issues. There is an opportunity to become even more creative, increasing the use of community parks and recreation programs to address health and social issues. The Advisory Council noted that parks can support activities similar to health clubs, for free. Dr. Deborah Cohen shared a study that reveals solutions to increase healthy physical activities in parks: The First National Study of Neighborhood Parks: Implications for Physical Activity published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine Volume 51, Issue 4, October 2016, Pages 419–426.

The Advisory Council recommended a statewide effort to inform decision makers and the public about why parks and recreation services should be expanded for public health and safety. "Create and celebrate your successes. If you can show that you are changing the community, people want to be a part of it" advised one participant.

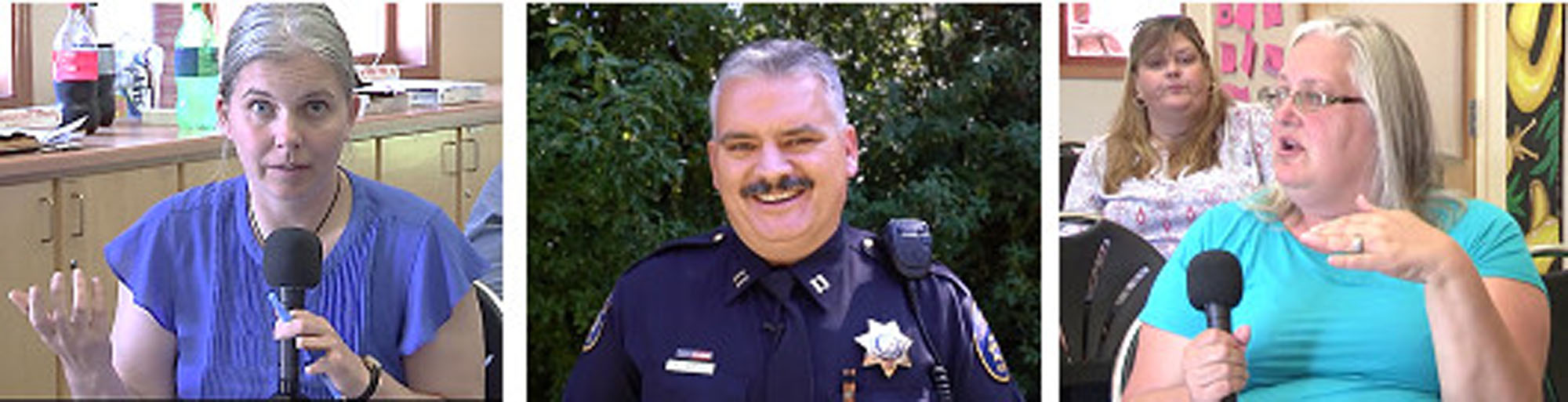

The Advisory Council also encouraged stronger partnerships with the health sector and law enforcement to develop new park projects and programs as an essential public health service.

Thirty Public Focus Groups

After the seven Advisory Council Focus Groups, 30 focus groups were conducted statewide in 2017. Nearly 500 members of the general public and university students participated in these listening sessions.

Methods

In preparation, initial contact was made with local park and recreation agencies and community-based non-profit organizations. DPR asked the local contacts if they would be interested to host a focus group for California's SCORP. Considering that the department was asking local contacts to host and invite the public, there was an effort to give flexibility to the host about who to invite and where to locate the meeting. DPR provided a sample flyer to help describe what questions would be asked of participants, and encouraged the host to invite a broad representation of the community including different age groups.

The discussions were framed around three questions designed to learn how Californians consider parks and recreation in their communities, especially from a health perspective. The questions were also designed to ground-truth and research the statewide concerns and opportunities referenced in this chapter by the 2016 Advisory Council. During each public focus group, DPR asked the participants these three questions:

1) The California Department of Parks and Recreation understands that there may be health and safety challenges within your community. What types of park projects or programs do you think can help, and why?

Goal: Including "health and safety" in the first part of the question was designed to encourage the public to think about parks and recreation from a health and safety perspective. This tested the Advisory Council Focus Groups' idea of considering parks and recreation as a public health and wellness service.

The second part of the question was intended to assess what types of projects — such as what type of facilities are desired — and programs are needed in local parks when "health and safety" is considered. Therefore, this question encouraged participants to share their vision for health and safety in parks.

Findings:

- More recreational programs were desired, especially art and music, sports, and multi-generational activities that specifically "bring families together." Parents felt disconnected from their children and were hopeful that programs in parks can help them reconnect.

- Daily presence of parks and recreation staff is also desired to help make the public feel welcome and safer in their local parks.

- Lighting for night-time use after school and work days and clean restrooms were consistently mentioned as critical to support extended use.

- To our surprise, answers tended to focus more on access to parks and recreation programs more than a specific type of park facility they would like in their parks.

2) Has a park or recreation program changed your life? How?

Goal: The question was designed for the public to share stories about why park and recreation matters in their life. This was a way of testing how the general public may relate parks and recreation to public health and wellness.

Finding:

- Participants shared heart-warming stories about how a recreation program inspired a new direction in their life, how they reached health goals at a park such as a walking track, and the importance of having a shared public space to socialize with other community members.

3) Is there anything else you want to tell state leaders about parks and recreation in your community?

Goal: The question was designed to encourage additional comments that may help us learn more about unmet needs or what is working well from the general public's perspective.

Findings:

- In some densely populated areas, participants felt they were landlocked and communities need more park space. A few participants in extremely dense communities even mentioned that streets could be closed and converted into parks, or parks should be built on rooftops.

- Designing parks to meet the needs of all age groups was a consistent request from all focus groups. Some participants felt their local park was only designed for children, and they had to travel too far to go to a park that offers what they need.

- Participants expressed that parks outside their communities are also important to preserve nature.

- Every focus group expressed gratitude for state and federal park development programs.

- After the focus groups, it was common for the host (local park and recreation agency contact) to explain with enthusiasm that the focus group helped provide new ideas and a deeper understanding of what the community needs. This is another indicator that community-based discussions between people that live near proposed projects and the park designer/provider are a valuable method to generate ideas and reach a more personal understanding of what the community needs.

SCORP Public Focus Group Locations

April 4, 2017

Public Focus Group: Friends of the LA River

Location: Los Angeles River — Frog Spot

April 5, 2017

Public Focus Group: Watts Community Residents

Location: Serenity Park, Watts

April 5, 2017

Public Focus Group: Avalon Green Team Residents

Location: Maya Angelou High School

"I really liked this change from an organizational group of young people, of children — they were painting the alleys. So then it was a really beautiful change and what I liked was the participation, it was the union that happened in the young people for the community — Equipo Verde."

April 5, 2017

Public Focus Group: El Monte Community Residents

Location: Zamora Park

Date: April 5, 2017

Public Focus Group: Our Parks Coalition

Location: Casa Italiana

"I think that a big issue isn't just increasing our urban parks, it is also increasing access to our wilderness and open spaces. It doesn't just mean providing busses for people to get to those places, but it also means making people feel welcome in those spaces."

Date: April 6, 2017

Public Focus Group: California State University Students

Location: CSU — Northridge

Date: April 5, 2017

Public Focus Group: Los Angeles Community Residents

Location: El Serrano Arroyo Playground

Date: April 6, 2017

Public Focus Group: City of Paramount Community Residents

Location: Paramount Community Center

—Aliccia

"Thank you for the outdoor gym equipment — I've become a very active resident and its saved me lots of money in gym fees."

Date: April 7, 2017

Public Focus Group: Anaheim Community Residents

Location: Brookhurst Community Center and Park

Date: April 10, 2017

Public Focus Group: Oakland Community Residents

Location: DeFremery Recreation Center

Date: April 11, 2017

Public Focus Group: California State University Students

Location: CSU — East Bay

"Parks are a great way to de-stress. There is a sense of peace when I am outside, I really like to appreciate nature and just be, and bask in what nature brings to us, and parks really helps with that. When I go outside I see the trees, I hear the birds, it is like a whole different feeling than when you are indoors, and it is a really good way to de-stress."

Date: April 11, 2017

Public Focus Group: East Bay Regional Parks

Location: Richard Trudeau Training Center

"Not all parks are alike. It is a skill set that needs to be mastered. It is an art form because there is no cookie cutter approach. It has to be the right park function, the right use for the community."

Date: April 12, 2017

Public Focus Group: San Francisco Community Residents

Location: Curry Senior Center

"I have an imagination… Build open spaces up! Create floors for parks and each floor could be for a specific need, first floor for children, and second floor for adults. This is San Francisco, it is a small place, maybe we could create 1st floor and 2nd floor parks."

Date: April 12, 2017

Public Focus Group: California State University Students

Location: CSU — San Francisco

I am today." — Lauren

Date: April 13, 2017

Public Focus Group: East Oakland Community Residents (Youth Group)

Location: East Oakland Youth Development Center

Date: April 12, 2017

Public Focus Group: San Francisco Community Residents (Youth Group)

Location: Boeddeker Park

— Charlie

Date: April 28, 2017

Public Focus Group: California State University Students

Location: CSU — Chico

Date: May 2, 2017

Public Focus Group: California State University Students

Location: CSU — Sacramento

Date: May 31, 2017

Focus Group: Health in All Policies Task Force

Location: Natural Resources Agency Building, Sacramento

August 8, 2017

Public Focus Group: Watsonville Community Residents

Location: Watsonville City Council Room

August 8, 2017

Public Focus Group: Together in Pajaro

Location: Pajaro Park

"Part of why the lunch program was created here, is that parent education isn't always what we would like to see. We have so many young parents here. These are kids who didn't get to finish growing up, and now they have to grow up so quickly. And we want to offer programs here to help them. We want to bring out parenting classes, classes to help with finances."

August 9, 2017

Public Focus Group: Gilroy Community Residents

Location: Gilroy Senior Center

August 28, 2017

Public Focus Group: Eureka Community Residents

Location: Sequoia Park Forest & Garden & Zoo

August 28, 2017

Public Focus Group: Eureka Community Residents

Location: Jefferson Project Park

"California must invest in children and the environment. Partnerships between law enforcement and parks and recreation and the community — we all need to work with our children — and it takes constant work!"

"The AB2060 program Release to Work and the partnership with Jefferson Project Park benefits include offenders getting jobs for the first time, developing skills and a sense of community, restoring individuals, and providing healthy and positive activities." —Chief probation officer

— Susan

August 28, 2017

Public Focus Group: Eureka Community Residents

Location: Jefferson Project Park

"Local parks are the real opportunity to encourage healthy living outdoors. Surveys revealed a very low percentage of kids visited a state park. Low income households found costs and transportation as barriers, this is why local parks are so important."

"The parks are our lungs. It cleans you to be at the park, physically, mentally, and spiritually. We need to use this space. Without this space there's tension, to not have access is part of the problem."

September 18, 2017

Public Focus Group: El Centro Community

Location: MLK Sports Pavilion

"State and local leaders need to make parks a priority. Having a healthy environment creates a healthy community, overall. Gives people the opportunity to interact and socialize, to bring something more than the "every day, let's go to work routine."

"Parks and recreation has changed my life for the better. I have seen the positive effect it's had on the community. The soccer program brought parents and even grandparents out to enjoy the park while children practice."

"The programs that the parks department offered when I was a kid gave me an outlet to be constructive, got me out of the Circle K playing video games and getting in trouble, and it led me to the person who I am today, and what I do now, being a part of the community and becoming a pediatrician. I think that I owe a lot to the parks and rec department."

September 19, 2017

Public Focus Group: Perris Community Residents

Location: Perris Senior Center

"It's obvious that parks and recreation are important in people's lives. We need more programs for all ages. They're important for all to feel included, to develop skills, and develop social groups that they can belong to. We need more funding to maintain and have new parks so more families can be reached."

September 20, 2017

Public Focus Group: Chula Vista Community Residents

Location: Parkway Community Center

September 19, 2017

Public Focus Group: Riverside Community Residents

Location: Bobby Bonds Park and Sports Complex

— Officer

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan From Focus Group Findings

The following priorities are based on key findings from the seven SCORP Advisory Council focus groups and the thirty public focus groups. LWCF projects will address at least one of the following priorities:

- New Park Access

- Create or expand parks in communities that lack sufficient park space. Create new parks within a half mile of underserved communities, or expand existing parks to increase the ratio of park acreage per resident in underserved areas. This may include innovative solutions such as acquiring private land from willing sellers such as vacant lots and blighted buildings, converting streets to create or expand parks, or converting closed schools.

- Acquire private land from willing sellers in natural areas to expand regional parks, or create new open space areas for outdoor recreation while preserving nature.

- Multi-Use Parks Designed for All Age Groups in New or Existing Parks

- Construct recreation features designed to bring families together by supporting art and music, sports, and multi-generational activities.

- Construct recreation features for all age groups to support different active and passive recreation interests of all ages.

- Incorporate project design ideas from all age groups.

- Health Design Goals for New or Existing Parks

- Include recreation features resulting from asking community members for their park design ideas for public health.

- Safety and Beautification for New or Existing Parks

- Construct lighting for night-time use, or restrooms, landscaping, signs, or other enhancements to make the park appear welcoming and support longer hours of use.

- Preservation

- Through the LWCF, place outdoor open space land under new 6(f)(3) protection for public recreation.

Public health, including environmental and social wellness, is fundamental to the mission and purpose of park and recreation providers.

For example:

- DPR's mission statement begins with: "To provide for the health…of the People of California…"

- The national LWCF Act of 1965's statement of purpose includes "…assuring accessibility to all…present and future generations…such outdoor recreation resources…to strengthen the health and vitality of the citizens of the United States…"

Parks are unique places where children can play, people exercise, seniors socialize, families and friends bond, youth are mentored, cultures are celebrated, and where everyone connects with nature. For these basic reasons, the nexus is clear between parks, recreation programs, and health.

However, while "health" gives the park and recreation sector a higher sense of purpose, the SCORP Advisory Council commented that local partnerships between park/recreation agencies and health agencies were generally uncommon.

The council believed California's 2021–2025 SCORP should encourage new partnerships between local health and park agencies. Therefore, the following approaches have been implemented.

Grant Incentives for Partnerships

Competitive grant program criteria is an effective method for encouraging local health and park agency partnerships. For example, competitive "Project Selection Criteria" points can be awarded to grant applicants for partnering with a local community health organization. By awarding points, the competitive grant applicants have an incentive to involve a local health organization in the planning, funding, design, and construction of a park project or operational programs and services.

This idea was presented to local park agencies in 2018–19 focus groups and public hearings for inclusion within the draft Proposition 68 SPP Application Guide. During the SPP focus groups and hearings, there was a broad concensus of support. The SPP Application Guide's "Project Selection Criterion #6" now includes partnership incentives for the grant applicant to involve a health organization during the planning, design, funding, or construction phase of the park project.

The SPP makes available significant park development funding for the construction of running tracks and walking loops, outdoor gym stations, sports courts and fields, community gardens that produce fresh food, amphitheaters for performing arts programming, swimming pools and aquatic features, skate parks and play areas, and natural areas.

Connecting Health and Park Agencies

DPR and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) can help introduce local health departments (LHDs) to park agencies.

-

Health agencies and other entities interested in partnering with local park agencies can contact DPR's Community Engagement Division via email at scorp@parks.ca.gov

. -

To find LHDs local park agencies can search the CDPH website by city or county under the Local Health Services page.

https://cdph.ca.gov/Pages/LocalHealthServicesAndOffices.aspx

California's Health in All Policies (HiAP)

California's Health in All Policies Task Force (HiAP) engages over 20 State departments to view each department's work through a public health lens.

During HiAP conversations, DPR's Community Engagement Division shared the belief that local parks, in communities, can become thriving resources for health especially when programs are offered to help activate the park. DPR further explained that in some areas, when an ideally located park has no programming and insufficient infrastructure, the park may be under-utilized. To test this theory, the "Active Parks, Healthy People" Pilot Program involved offering a program in a park and testing if it will lead to increased physical activity for health and wellness. Details and findings from the Pilot Program are included in the next few pages.

Active Parks, Healthy People Pilot Program

In 2019, the Nutrition Policy Institute developed and implemented an Active Parks, Healthy People Pilot Program in three California counties (Fresno, Los Angeles, and Stanislaus) to explore whether offering a structured physical activity opportunity in community parks would enhance park utilization and increase program participants' physical activity levels.

Participants rated the classes highly. Although some increases in physical activity among park users and program participants were observed, the number of participants were too small to arrive at definitive conclusions. Challenges recruiting participants led the research effort to focus on barriers to park program participation.

Lack of childcare and park safety were the top barriers cited by participants. Health department staff and their partners report that a two-pronged approach that includes both 1) improvement to park infrastructure and safety and 2) support for long term, community-tailored park programming is needed to address barriers to park use and create physical activity opportunities that best fit community need.

The Active Parks, Healthy People Pilot Program report discusses, on page 13, the three communities reported that getting community members out to the park for a program or activity is a good idea for increasing park use.

The evaluation report's quotes from stakeholders provide a personal validation to the concept. Specifically, the quotes on page 16 about the benefits of giving residents a leadership role, and building trust over time through sustainable programming, are especially important.

This is a direct response to the work and conversations that originated in the Health in All Policies (HiAP) parks and green space workgroup.

"It's just getting programming at the park and getting people to see that it's being used and being used for positive things. You know like leagues for kids or even for adults. It's just getting rid of that stigma that the park is abandoned, and it's only used for crime."

— Stanislaus County stakeholder

The report is available on the Nutrition Policy Institute's website: https://npi.ucanr.edu/Publications

Gerstein DE, Plank K, Woodward Lopez G, Crawford P. Active Parks, Healthy People Pilot Program, Evaluation Report. Nutrition Policy Institute. May 2019. https://ucanr.edu/sites/NewNutritionPolicyInstitute/files/310880.pdf

Facilitators of Park Use and Program Engagement

- Park amenities such as access to walking trails, play equipment, lighting and clear signage

- Presence of sustained park programming

- Programs designed based on community input and fit well with the physical space and available amenities of the park

- Community gatekeepers to promote programming

- Social connectivity built through program participation

Barriers to Park Use and Program Engagement

- Restrictive use policies of community parks

- Lack of park amenities and sustainable programming

- Park reputation as unsafe

"There is a city ordinance that people can't be out at parks at night."

– Stanislaus stakeholder

"It's just getting programming at the park and getting people to see that it's being used and being used for positive things. You know like leagues for kids or even for adults. It's just getting rid of that stigma that the park is abandoned, and it's only used for crime."

– Stanislaus stakeholder

"The reputation of a park can play a big role (in park usage)"

– Fresno stakeholder

"Some other parks are well-lit parks and they will go to those parks because they feel safe."

– Fresno stakeholder

"[Program Participants] got to know each other...They became friends and I think after the exercise class ended, they kept in touch and they kept exercising."

– Los Angeles stakeholder

"It's sort of a vicious cycle because folks don't go to the park because there's no programming and...there's no programming because folks don't go to the park."

– Los Angeles stakeholder

Examples of Health and Park Agency Partnerships

In 2019, a study from the University of California, Los Angeles Institute of Environment and Sustainability found "Park Prescription" programs are an example of community public health infrastructure in action. This study further found that information about parks can be integrated into healthcare providers' electronic records systems. Pediatricians can search for parks based on their patients' locations and interests and write prescriptions for park use. Park Rx programs have been shown to increase the number of families who visit parks, the days per month that people spend in parks, and the time they spend physically active. There are currently more than 20 park prescription programs across California. Collaborating with healthcare providers represents a growing potential.

Citation: Christensen J, Rigolon A, Robins S, and Alemán-Zometa J. California State Parks: A Valuable Resource for Youth Health. UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. September 2019.

https://www.ioes.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/UCLA-report-on-California-State-Parks-and-Youth-Health.pdf

In 2011, the Healthy Parks Healthy People (HPHP) was created with the goal of improving the well-being of Bay Area residents through over 50 park, health, and community organizations. Health-focused programs include family fitness classes, guided hikes and nature walks that provide free introductory experiences for first time or infrequent park visitors. HPHP Bay Area piloted "Park Prescription" programs where health care and social service providers encourage their patients to take advantage of First Saturday and other programs to get into the parks for their health and well-being. As of 2018, each of the nine Bay Area counties are designing and implementing their own Park Prescription programs.

In Los Angeles, the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation launched Summer Parks After Dark (PAD) at 33 county locations, with free programs and events for children and families. In 2018, the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA) awarded PAD with the Best in Innovation Award. PAD is led by the county's Department of Parks and Recreation, with strong support from partners including the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, Chief Executive Office, Sheriff's Department, Department of Mental Health, Department of Public Health, Department of Workforce Development, Aging and Community Services, Probation Department, Department of Children and Family Services, and many community-based organizations.

The Summer PAD programming ranges from concerts in the park, summer Olympics, art classes, bicycle workshops, CPR/First Aid training, walk/run events, gardening classes and sports clinics, etc. PAD started with only three parks in 2010. Since then, the program expanded to 33 parks in 2019.

Other health-in-parks findings:

- In 2018, California's Proposition 68 reported that "the California Center for Public Health Advocacy estimates that inactivity and obesity cost California over $40 billion dollars annually, through increased health care costs and lost productivity due to obesity-related illnesses, and that even modest increases in physical activity would result in significant savings. Investment in infrastructure improvements such as biking and walking trails and pathways, whether in urban or natural areas, are cost-effective ways to promote physical activity."

- Adults and youth who live close to parks experience higher physical activity levels. An international study by the University of Exeter's Medical School (Environ. Sci. Technol., 2014, 48 (2). pp 1247–1255) also found that parks nearby provide psychological benefits — as much as a one-third decrease in mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression.

- In distressed neighborhoods where vacant lots were converted into small parks and community green spaces, residents reported significantly less stress and more exercise, according to a 2011 study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

- "Children and families are more likely to consistently exercise when in groups or social environments. Providing easy to use equipment dramatically increases physical activity and improves the well-being of most parks" said Frank Meza, MD, Kaiser Permanente's East Los Angeles Medical Center.

- A study of 174 neighborhood parks found that marketing, programming, plus active design, can result in up to 63% more hours of physical activity per week in parks by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Volume 51, Issue 4, pages 419–426).

Public parks and recreation opportunities serve as gateways to a healthier America. Parks provide affordable places to exercise. Youth join teams, and cultural celebrations such as concerts, dances, and other performing arts occur in parks. Parks serve as strong catalysts in reclaiming urban run-down areas, and even contribute to environmental health — where landscaping can clean air pollutants and clean stormwater runoff.

A Public Wellness Intervention

Health and Safety Benefits of Parks and Recreation Programs

Physical and Mental

- Affordable alternative to private health clubs through outdoor gym equipment, calisthenics zones, tracks, sports courts, and fields.

- Youth and adult sports leagues for physical fitness, sense of belonging, team work, esteem.

- Release stress, places to exercise and play.

- Therapeutic recreation, a place for people to heal from illnesses and trauma.

- Wellness resource, place for social services like health screenings and nutrition/meals.

- Places to connect with nature and be outdoors.

Economic

- The outdoor recreation industry in California generates $85.4 billion in annual spending, and $6.7 billion in state and local taxes. It helps support 732,000 jobs and internships, in construction, maintenance, program, lifeguards, rangers, vendors, and administrative staff.

- Higher property values.

- Tourism revenue.

- Concessionaire, equipment rentals, and sales revenue for sports leagues, camping, boating, skiing, hiking, surfing, biking, boating, and motorized recreation, etc.

Why intervene?

- Physical inactivity

- Diabetes, obesity, heart disease

- Social isolation, time spent indoors

- Unemployment, crime, stress

- Air pollution

Environmental

- Parks adjacent to schools, and active transportation/safe routes to schools, such as bikeways, trails, and greenways, create healthier city environments.

- Tree canopies improve air quality, provide shade, and reduce heat island effect.

- Resources for environmental education and conservation.

- Natural resource protection and wildlife habitat.

- Natural watershed for urban storm water runoff.

Social and Cultural

- Events and programs bring the community together, create social cohesion, and opportunities for volunteerism.

- Family bonding, a place for families to spend time together.

- Safer communities, programs offer positive alternatives to gangs and drugs.

- Police and the public can improve relationships through parks and programs.

- Art, music, dance, and theatre activities for cultural enrichment.

- Mosaics, murals, and sculptures created by residents or that depict the community's culture and history help build a "sense of place."

- Community gardens to grow healthy foods.

- Cultural resource protection.

- Inclusion, parks can serve all ages, ethnicities, incomes, and physical abilities.

- Increases cultural connections by promoting cultural understanding.

What Works?

Four Keys to Increase Healthy Park Use

Provide access to a park

When people have access to parks, they exercise more. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has called for more parks and playgrounds. Residents need time and money to travel to parks away from their communities. Only a park within a community can provide immediate daily access for its residents.

Consider Design

- Parks and programs can become more popular when youth, seniors, and parents—who are experts about their community's needs—give ideas for recreation features, park layout, beautification, program times and safe public use. This also creates ownership and connects residents with their local government.

- Walking loops, gymnasiums, sports fields and courts, and fitness zones generate the highest amount of physical activity in parks.

- Passive recreation areas with trees, community gardens, and open space give residents a place to connect with nature, reduce stress, grow healthy food, socialize, and beautify a community. These areas also reduce the urban heat island effect (where pavement and other hard surfaces raise temperatures).

- Amphitheaters and public art such as mosaics and murals support community festivals, cultural cohesiveness, and enhance a "sense of place."

A study of 174 neighborhood parks found that marketing, programming, plus active design can result in up to 63% more hours of physical activity per week in parks.

Cohen, D., et al. The First National Study of Neighborhood Parks: Implications for Physical Activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, (October, 2016) Volume 51, Issue 4, pages 419–426

Offer Programs

- A programmed park is a safe park. Offering supervised programs can quickly turn underused parks into thriving health zones.

- Exercise groups such as aerobics and tai-chi attract new visitors and increase physical activity in parks.

- Coaches and sports leagues give a positive sense of belonging for youth, teach teamwork, and bring the community together.

- Music, dance, and other art programs can offer students alternative forms of physical activity and can be ideal for family weekend events.

- Social services, meals, job training, and health screenings can happen in parks.

Market to the Community

Make residents aware of programs through use of banners, the media, and other outreach efforts.

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for Health Partnerships

- Encourage partnerships between health and recreation sectors through grant programs. Partnerships between health and recreation sectors may include:

- Outreaching to local community members during the community-based planning process.

- Providing feedback on how parks can be designed to support healthy lifestyles.

- Leveraging resources for acquisition and construction projects, program services, and site maintenance.

-

At the state level, DPR OGALS can connect local health agencies to local park agencies due to current contact with over 700 local park agencies. Requests may be sent to scorp@parks.ca.gov

with a description of the desired target area and any relevant information about goals and priorities.

State Agencies and LWCF

The 2021–2025 SCORP provides an Action Plan for state agencies that are eligible to receive LWCF funding. California's Public Resource Code §5099.12 establishes how the annual federal apportionment is allocated. The following sets a plan for California's state agencies that are eligible to receive LWCF funding per California's Public Resource Code §5099.12.

Crystal Cove State Park $1,000,000 LWCF grant in 1983–1984 for development.

Mount Tamalpais State Park $734,000 in 1971–1972 for acquisition.

State Parks

With 280 state park units, over 340 miles of coastline, 970 miles of lake and river frontage, 15,000 campsites, and 4,500 miles of trails, California's state parks contain the largest and most diverse recreational, natural, and cultural heritage holdings of any state agency in the nation.

In 2015, a report named A New Vision for California State Parks , provided recommendations which led to State Parks Final Transformation Progress Report (May 2017). This completed process is informing this current SCORP. State Parks is also engaged in a new planning process called "A Path Forward 2026" which will inform future priorities.

The 2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for California State Parks LWCF Projects

These priorities, which are also applicable to LWCF projects, were derived from the Transformation Action Plan and the Parks Forward Commission's Vision.

LWCF State Park projects must provide for public outdoor recreation and meet at least one of these priorities.

- Protect and enhance California's iconic outdoor landscapes and natural resources through projects that are accessible to Californians while welcoming visitors from around the world.

- Engage and inspire younger generations.

- Promote healthy lifestyles and communities.

- Create meaningful connections and relevancy to people.

- Work with new and existing partners to improve and expand facilities, and garner more resources (such as matching funds for LWCF grants).

- Expand park access for all Californians.

Department of Fish and Wildlife

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) manages and protects the state's fish, wildlife, plant, and native habitats upon which they depend. CDFW is responsible for related recreational, commercial, scientific, and educational uses. CDFW joined with the California Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) to develop WCB's 2014 Strategic Vision Plan (Plan). A 2019 Plan Update outlines the ever-changing wildlife, fisheries, hunting, and state conservation policies to meet both departments overall missions and objectives. Both WCB and CDFW work cooperatively to implement mutual conservation efforts.

Wildlife Conservation Board

WCB was created by legislation in 1947 to administer a capital outlay program for wildlife conservation and related public recreation. WCB is a separate and independent board with authority and funding to carry out an acquisition and development program for wildlife conservation. The primary responsibilities of WCB are to select, authorize and allocate funds for the purchase of land and waters suitable for recreation purposes and the preservation, protection and restoration of wildlife habitat, which includes authorizing the construction of facilities for recreational purposes on property in which it has a proprietary interest.

In 2014, the WCB revealed its 2014 Strategic Plan (Plan). The Plan described a series of goals, strategic directions and objectives, and priorities centered around public access and conservation investments. The Plan continues to serve WCB well, however, since the art and science of conservation changed substantially during the last five years, an update to the Plan was created in 2019 to capture those changes. The 2019 Plan Update was created to align new strategic initiatives and objectives with current and anticipated funding sources, public conservation policy, and current conservation trends. Within the 2019 Plan Update, these five objectives emphasize efforts to continue public access work and embrace new access modes and opportunities.

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for WCB and CDFW LWCF Projects:

For both the WCB and CDFW, LWCF projects must provide for public outdoor recreation access, and meet at least one of these priorities:

- Invest in projects providing public access for disadvantaged or severely disadvantaged communities.

- Invest in projects providing boating/fishing/hunting access to disadvantaged communities and providing additional facilities for mobility-impaired visitors and/or access compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

- Invest in projects that provide hunting or fishing opportunities.

- Invest in projects that have a primary or secondary purpose of non-consumptive wildlife recreation, such as bird watching or hiking.

- Conduct community meetings, with one being in a disadvantaged community, that provides information on a project and the availability for public input.

- Acquisition and restoration projects in areas identified as habitat for vulnerable species or as highly resilient to climate change.

- Increase habitat for sensitive species to support biodiversity through statewide protection or restoration of oak woodlands, riparian habitat, rangeland, grazing land, and grassland habitat.

Department of Water Resources

The Department of Water Resources (DWR), under the California Natural Resources Agency, manages California's water resources, and infrastructure, including the State Water Project (SWP). DWR operates and maintains a complex water storage and supply system, transporting water more than 600 miles from north to south in California. The following Action Plan items come from DWR's responsibilities and duties, as well as different plans including the State Water Project (SWP), the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Reduction Plan, and the Urban Water Management Plans (UWMP).

2021–2025 SCORP Action Plan for DWR's LWCF Projects: DWR projects for LWCF must provide for public outdoor recreation access, and meet at least one of these priorities:

- Provide for one or more of the following recreational opportunities, including but not limited to camping, boating, water skiing, swimming, hiking, bicycling, picnicking, fishing and hunting.

- Ensure public safety.

- Restore habitats.

- Meet the GHG emissions reduction goals and strategies for the near-term (present to 2020) and long-term to 2050 per Phase I of the GHG Emissions Reduction Plan.

- Reduce landscape water by using recycled water per the 2015 UMWP Guidebook.

State Coastal Conservancy

The State Coastal Conservancy (Conservancy) is a state agency, established in 1976, to protect and improve natural lands and waterways, to help people get to and enjoy the outdoors, and to sustain local economies along California's coast. The Conservancy is a non-regulatory agency that supports projects to protect coastal resources and increase opportunities for the public to enjoy the coast. The Conservancy also is responsible for the following:

- Implementing statewide resource plans through its projects, including the California Water Action Plan, the Wildlife Action Plan, and many others.

- Working along the entire length of California's coast and within the watersheds of rivers and streams that extend inland from the coast.

- Working throughout the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area and the entire Santa Ana River watershed.

- Providing technical assistance and grant funding to local communities, nonprofit organizations, other government agencies, businesses, and private landowners to implement multi-benefit projects, including protecting the natural and scenic beauty of the coast, enhancing wildlife habitat, and helping the public to get to and enjoy beaches and parklands.

The Conservancy's Strategic Plan, 2018–2022, communicates the role of the Conservancy in protecting coastal resources for all Californians, particularly underserved populations, such as disadvantaged communities, persons with disabilities, tribes, and others that disproportionally confront barriers to health and well-being and face increased vulnerability to environmental issues. The complete Strategic Plan can be viewed at https://scc.ca.gov/files/2019/10/Strategic-Plan-2018-2022-AB434.pdf

The following goals are found in both the Coastal Conservancy's Strategic Plan and the Explore the Coast Overnight Assessment of Low-Cost Coastal Accommodations Report. The complete assessment report can be found here: https://scc.ca.gov/files/2019/10/Explore-the-Coast-Overnight-Assessment-AB4343.pdf