Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning

Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP)

Purpose

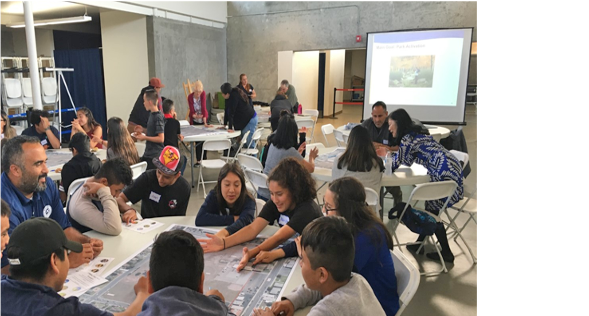

This document inspires meaningful community engagement for future public projects. It shares methods learned through California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP). These methods have been proven effective in urban, rural and suburban settings. This effort resulted in over 100,000 residents participating in the development of more than 1,300 project proposals during three rounds of competitive applications.

This park design community planning document is dedicated to...

- The next generation of policy makers, health advocates, and community planners who will work on future public projects. May the guiding principles in this document inspire all Californians.

- The over 100,000 neighborhood residents who shared ideas at community park design meetings. Thank you for your civic engagement.

- The over 1,000 park professionals who shared insight at SPP focus groups, public hearings, and application workshops. Thank you for your public service.

Table of Contents

Summary

Evolution of Community Engagement in Grant Programs

2000 to 2005

Creating the SPP Community Planning Model

Defining Core Terms

Learning Community-Based Planning Through SPP

1. Schedule Five Accessible Meeting Locations and Times

2. Invite a Broad Representation of Residents

3. Conduct Five Meetings to Achieve Three Park Design Goals

Park Design Goal 1 — Selection and design of recreation features

Park Design Goal 2 — Location of selected recreation features

Park Design Goal 3 — Safe public use and park beautification ideas

4. Documenting the Outcome

Building Social Capital, Cohesion, and Capacity

Inspirational Community Quotes

Find Talent in Residents During the Community Planning Process

Future Planning Efforts

Historical significance

California's SPP is the country's largest state-administered grant program for community parks. This historically significant grant program provided more than $1 billion in grant funding through Proposition 84 in 2006 and Proposition 68 in 2018.

All photos in this document are authentic to SPP and used with permission from grantees.

About us

Since 1965 over 7,580 parks have been created or improved with grants administered by the State Parks' Office of Grants and Local Services (OGALS). OGALS is a division within State Parks. Currently, more than 700 local agencies partner with OGALS in an effort to improve the health and wellness of California's almost 40 million residents by providing close to home park access.

Summary

Designing Parks Using Community-Based Planning Methods from California's Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program (SPP)

With $1 billion in local assistance grants, SPP is creating park access in underserved areas throughout California. SPP's grant guidelines, written with feedback from hundreds of local park agencies and nonprofit organizations, led to the development of a three-step public engagement model for designing community parks.

The steps include:

- Scheduling five accessible park design meetings at or near the project site, at different times including weekends or evenings.

- Inviting and involving youth, seniors, and families living in the project area to engage in an active planning process.

- Conducting interactive and dynamic meetings to achieve these park design goals includes:

- Selecting and designing recreation features.

- Locating the selected recreation features within the park.

- Identifying safe public use and park beautification ideas.

To inform future planning efforts over the next five years, State Parks and OGALS will continue to share successful methods learned through this SPP model.

This process encourages meaningful engagement between neighbors, local government, and organizations. These steps lead to authentic park designs representing each community's unique recreation needs and values.

Historical Significance of SPP Community-Based Planning

This document shares community-based planning methods learned through three competitive funding rounds. SPP has funded the creation of 130 new parks and 60 park expansions or renovations throughout California since 2010. With $5.2 billion in grant requests received for $623 million in available funding between three rounds, thousands of residents became civically engaged in their local park designs.

SPP Rounds One and Two: Proposition 84 (2006 Bond Act) made $368 million available for SPP grants. Nine hundred project proposals were received requesting $2.9 billion.

SPP Round Three: Proposition 68 (2018 Bond Act) made $650 million available for SPP grants. Round Three made available $254.9 million. On August 5, 2019, four hundred seventy eight (478) project proposals were received requesting $2.3 billion.

SPP Round Four: The remaining $395 million of Proposition 68 SPP will be awarded through a Round Four competitive process in 2020/21.

"Before and After" SPP project photos

Below are two examples showing how SPP projects transform communities. To see more statewide "Before and After" photos, visit www.ParksforCalifornia.org/projects

Evolution of Community Engagement in Grant Programs

Through 20 years of focus groups, public hearings, application workshops, and project site visits with local government and nonprofit organizations, State Parks analyzed community-based planning methods for park design. This section highlights the historic statewide success in developing a workable, community-based planning model for park design.

2000 to 2005

From 2000 to 2005, OGALS administered approximately $2 billion in local park construction projects funded by Proposition 12 (2000 Bond Act) and Proposition 40 (2002 Bond Act). Through discussions at project site inspections, OGALS began to discover differences between how some projects were designed and the value of asking neighborhood residents for park design input before projects were built. Engaging residents in park design increased care for the park and decreased vandalism. OGALS learned from various community groups the importance of creating a sense of ownership, and its powerful impact on a park's long term success.

During this period, OGALS started introducing competitive grant program criteria to evaluate whether a project's design included a "significant," "average," or "minimal" range of ideas from neighborhood residents. Grant applicants often asked what was needed to include a "significant" range of residents' ideas. However, specific goals and technical assistance for community-based planning were not available for competitive grant applicants during this timeframe.

During this early era, the department also learned of challenges with using traditional council, board and commission meetings as park design sessions due to the following reasons:

Time: Meetings held during daytime work hours were difficult to access for working adults and parents.

Location: Meetings outside project neighborhoods were difficult for seniors, youth, and economically disadvantaged residents to access due to a lack of private transportation and practical public transportation options.

Facilitation: Council and commission meeting agendas generally include other local government topics that differ from a park design workshop format.

Creating the Statewide Park Development and Community Revitalization Program

The passage of Proposition 84 (2006) Bond Act and Assembly Bill 31 (2008) created the SPP. SPP statute is found in California Public Resources Code §§5640 through 5653. SPP provides funds for land acquisition and development to create, expand, and improve parks in underserved communities. It also gives priority to "project applicants that actively involve the public and community-based groups in the selection and planning of the project."

The passage of these measures presented an opportunity to develop and introduce a new strategy for crafting a community-based planning formula with clear and specific goals. In 2008/2009 when the new strategy was introduced to focus groups and at public hearings, there was some public resistance. Some potential applicants shared the following concerns:

"We have had meetings in the past and no one shows up." "We do not have a meeting space in the project area." "The public are not park designers."Because of the initial concerns presented from the public, the SPP Team challenged hundreds of park professionals at thirty statewide focus groups and public hearings to offer solutions and feedback on the proposed community-based planning goals. Solutions were added to a technical assistance section for grant applicants within the SPP Application Guide. The final guidelines were adopted, and SPP served as an effective touchpoint for residents, local government agencies and community organizations to collaborate in park design efforts that embraced the spirit, needs and culture of communities statewide.

According to residents, park design meetings held in their neighborhoods helped them develop personal connections with their local government and neighbors. Park directors, staff, and city managers shared their satisfaction with working with their constituents and how residents' ideas contributed to the better project design. This process encourages a thoughtful exchange of knowledge by professional project managers who offer technical expertise, and neighborhood residents, who offer insight about their community's needs based on their daily life experiences.

"What we have seen in this process is a working partnership between our residents and our city. When residents take part in the planning of a park and provide their own input, and the city responds in kind, both sides take ownership of the project and benefit together. It's a win-win for everyone."

Richard Belmudez | City Manager, City of Perris.

"This model is a standard for community empowerment that leads to healthy, livable, and viable communities. SPP projects in underserved communities create a sense of place while promoting social justice through equity of and access to close-to-home parks. When community residents are engaged in a local park's design, residents become more likely to appreciate the role parks play in their daily lives. With that appreciation, park advocacy increases."

Sedrick Mitchell | Deputy Director, Community Engagement Division (CED), State Parks

"Authentic community engagement is critical to ensure a design that reflects the community's needs and priorities for parks in their neighborhoods."

Alina Bokde | Deputy Director, Planning and Development, County of Los Angeles Parks and Recreation

Defining Core Terms

Clarity and guidance are crucial for the success of the collaborative process. Having universal terms allows for consistency and promotes participant creativity. In this model, three core definitions are: "residents," "broad representation," and "meetings." In summary, these definitions guide planners to meet with a representative cross-section of groups surrounding the project. These definitions also encourage dynamic park design discussions resulting in popular parks that serve multiple generations.

"Residents" is defined as "the population living within a half-mile of the project site including youth, families, and seniors."

What is the intent behind this definition?

Defining 'Residents' guides park planners to focus their engagement on those who live within walking distance of the project and are most likely to be affected by the benefits and potential challenges of living close to public spaces. Engaging residents has proven to be critical for these reasons:

- Studies have shown that people use the parks closest to their homes more frequently; and,

- People who live in neighborhoods nearest to the project site are experts about what the community needs, including ideas for safe public use; and,

- Residents living within walking distance may feel a sense of ownership over the park, and are more likely to actively monitor and contribute to the upkeep and safety of the facilities.

Encourage engagement of all age groups to design a park that serves multiple interests in the community.

"Broad Representation" is defined "inclusion of design ideas from residents that may have different recreational needs, including youth, seniors, and families. Inclusion of people with disabilities, single adults, and immigrants is also encouraged. The sole involvement of an advocacy group or league likely to promote a specific recreation feature does not meet this intent."

What is the intent behind this definition?

This definition guides park planners to encourage a dynamic discussion that considers the varied interests of the community. Park designs that incorporate various interests and meet a wide range of needs will likely be more popular and heavily used.

"Meeting" is defined as "residents working together as a group in person with the applicant or with the applicant's partnering community-based organization(s) to design the park. This type of meeting can be creative, cost-effective, and non-traditional. Formal public hearings are not required."

What is the intent behind this definition?

This definition guides park planners to encourage brainstorming and group thinking. By supporting dynamic group discussions, residents will often build off of each other's ideas; resulting in project designs that more accurately reflect their collective vision. Things to consider:

- If an organization lacks experience in organizing community focused meetings they may consider partnering with community-based organizations to assist with engaging residents.

- Consider innovative approaches to make park design meetings with residents interactive and dynamic.

Learning Community-Based Planning Through SPP

SPP's community-based planning model involves conducting five accessible and interactive park design meetings with a broad representation of residents. This chapter provides detailed guidance about how to make meetings accessible for residents, how to invite a broad representation of residents, and how to achieve park design goals during the meetings. This community-based planning model includes the following:

1. Scheduling Five Accessible Meeting Locations and Times

The first community-based planning step involves strategizing how to make meetings as accessible as possible for residents.

2. Inviting a Broad Representation of Residents

The second community-based planning step involves strategizing how to welcome all age groups to the meetings.

3. Conducting Five Meetings to Achieve Three Park Design Goals

The third community-based planning step involves strategizing how to conduct dynamic meetings where residents work together to share park design ideas.

The following goals lead to an authentic and vibrant park design that is unique to the community's insight and needs.

Park Design Goal 1 – Selection and design of recreation features. Park Design Goal 2 – Location of selected recreation features. Park Design Goal 3 – Safe public use and park beautification ideas.4. Document the Outcome

A site drawing and list of accepted design ideas informs the project's construction phase.

1. Scheduling Five Accessible Meeting Locations and Times

To increase participation, it is important to schedule meetings close to the project area's neighborhood residents. Also consider residents' work or family schedules. This section provides detailed guidance on how to make meetings accessible for residents.

From the SPP Application Guide:

"The applicant or partners facilitated at least five meetings, between June 5, 2018, and the application deadline, to obtain ideas from the residents."

Why five meetings?

During SPP focus groups and public hearings, participants indicated that five meetings were a reasonable amount to accommodate the needs of residents with various employment schedules. Participants also felt that meetings should be relatively recent to ensure that recommendations meet the needs of current residents.

Location Access: Meeting locations should occur, if possible, at the project site or within the project site's half-mile radius. By listening to the residents who live nearest to the project site, and incorporating their ideas, a sense of ownership is fostered which can strengthen the project's long-term success. Scheduling accessible meeting locations is also critical for increasing residents' participation. Meetings held outside the project area require additional transportation resources and travel time, which can make it more challenging for residents to access.

The phrase "or within a convenient distance" allows for some flexibility in rural areas in cases where there are no neighborhoods within a half-mile walking distance of the project site. If, however, a neighborhood or school exists within the project area's half-mile radius, every effort should be made to schedule meetings close to the project site. When facilities are available, conducting meetings outside of the project area should require substantial justification.

From the SPP Application Guide:

"The meetings were located within the critically underserved community, or within a convenient distance for residents without private transportation."

"At least two of the meetings occurred on a weekend or in the evening."

Dates and Time Access: Providing five meeting opportunities for people with varying work or family schedules is challenging, but essential. Schedule at least two of the meetings during evenings or weekends. Please read the guidance below to learn about scheduling meetings on a weekend or in the evening.

"In the evening": Weekdays helps to reach working people who may not be able to meet from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. A 6 p.m. or later start time may accommodate people who are commuting from work and picking up children on their way back to their neighborhood. Meetings with students at school or from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. after school may be ideal for youth. A morning to midday meeting might work well for elders.

"On a weekend": Weekend meetings target all groups and allow for multi-generational work sessions.

Application Tip: Scheduling meetings well in advance of an application deadline, will likely strengthen your application, since the content of your application will be rooted from a community-based process. Places to meet: Community leaders or residents might help identify the best meeting locations and times. Cost-effective strategies for meeting locations, dates, and times include:

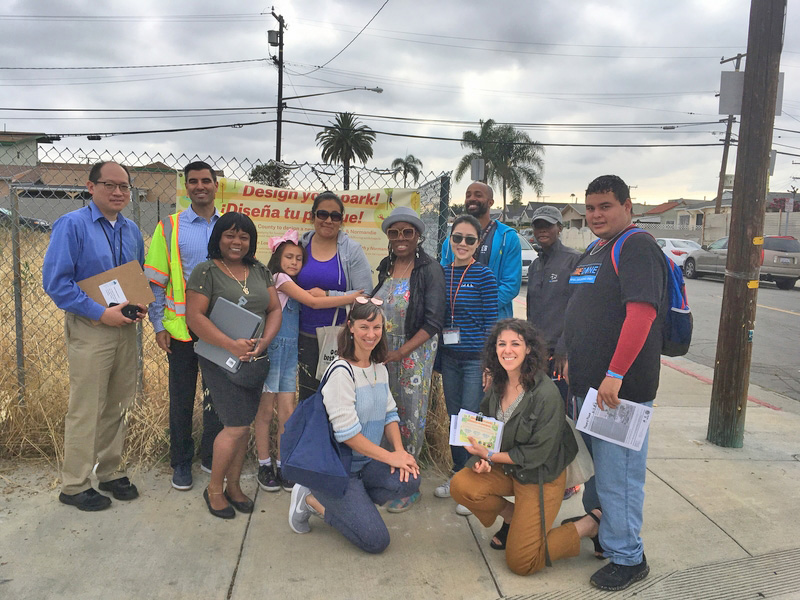

- Sidewalk meetings at the proposed project site are an effective way to have a meeting within walking distance for the residents. Applicants or a partnering community group can set up a banner, easels, and tables on a weekend morning. Applicants can canvas neighborhoods in advance and on the day of the meeting to invite residents to attend. Organizers should go door-to-door inviting residents to walk to the site and join their neighbors to discuss park design ideas.

- Community-based organizations, schools, libraries, faith-based organizations, and restaurants, such as pizza parlors, may agree to provide meeting space.

- Go to where people meet: Take meetings to where people are already congregating. Examples of taking meetings to residents include:

- Collaborating with a school to schedule a meeting with classes.

- Adding to the agendas of neighborhood/community-based organization meetings where residents will be available.

- If there is a 55+ neighborhood area, try scheduling a meeting there. Or, try collaborating with a Senior Nutrition Program.

- Event Participation: Engaging residents at community festivals, shopping centers, farmers' markets, and other events are useful, especially if the event is within walking distance of the project site. While this method should not be the only modality utilized for gathering community input, it can be used to get feedback on ideas that may be generated from previous community meetings. In these types of settings residents typically approach event booths one at a time. It is, therefore, important to be creative in your booth design to allow residents an opportunity to provide input that continues to clarify the collective desires of the community.

- Survey: A survey may be used during the process but is not a "meeting" by itself. In other words, it can be a tool for gathering data but does not replace the value of brainstorming together, where insight shared by one participant can spark additional ideas and contributions from others.

"We've held meetings at school cafeterias or libraries where that part of town feels more comfortable in attending, rather than going to City Hall for instance."

Mikal Kirchner | Recreation and Community Services Director, City of Selma, California

"[The process led to] building a stronger relationship with the community, particularly the McKinley Elementary School parents and faculty and families living near the park."

John Alita | Director of Community Services, City of Stockton

"Having community engagement meetings at project sites shows people the relationship between the site and design, adds a level of reality, and really helps the community be able to start visualizing their design. It is a fun and unique way to gather input and increase community interest and participation. People who are driving or walking by tend to want to know what is going on. It's another way to get people involved. We witnessed people passing by stop in to join community meetings happening on the site and then went on to contribute to the project design by adding their comments. This is an approach that can be adopted readily and really pays off in the end."

Todd Schmit | Section Head for Landscape Architecture and Design, Planning and Development Agency, County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation.

"Being able to meet in the park (project site) is key. Walking around and visualizing elements is less abstract than a paper exercise. It also helps the project planners with thinking through issues by bringing users directly to the site and asking, what about this? What about that? Users will typically teach you how it should work or poke holes in your plans. Physically communicating and exploring your project is crucial to the design process which can sometimes be done in a vacuum, to the detriment of the project."

Travis Menne | Community Projects Manager, City of Redding, Community Services

2. Inviting a Broad Representation of Residents to the Meetings

After scheduling meeting locations and times, the second step is to reach a Broad Representation of Residents. Inviting a Broad Representation of Residents is essential for attendance as well as ensuring diverse input. This section explains how to notify and invite a broad representation of residents to participate in the meetings.

From the SPP Application Guide: "For the combined set of meetings, at least three methods were used to invite a Broad Representation of Residents." Guidance for inviting different age groups of residents are listed on the next page.

From the SPP Application Guide: "The number and general description of the Residents who participated in the combined set of meetings consisted of a Broad Representation of the critically underserved community."

This step encourages applicants to engage all age groups, including youth, seniors, and families within the project area. The goal is to get perspectives so the park is designed to meet a broad range of needs.

A reasonable number of residents in the project area should participate in the meetings. However, in heavily urbanized communities, over 20,000 people may live within the project's half-mile radius, while in rural areas, 100 people may live in a half-mile radius of the project.

What is an appropriate number of meeting participants? In general, past SPP applicants engaged approximately 30 to 300 residents between five meetings.

Successful outreach requires thoughtful planning. To increase participation, residents should be contacted at least one week prior to a meeting. Successful outreach should help lead to a Broad Representation of Residents.

"We learned that the in-person outreach received the most feedback compared to the online survey method. It is important to have multiple methods for feedback; however, our community didn't have a large response online."

Noel Castillo | Public Works Director/City Engineer, City of Montclair

"At each door, staff personally invited each resident to attend and explained why it was important. Given the feedback from the public online and at the meetings, staff believes that the electronic postings and newspapers were effective to provide notice but not necessarily to convince them to act. Quite a few of the individuals who attended the meetings in the parks said they attended because of a visit by a staff member. Just one attendee in all the meetings stated that he came to the meeting specifically due to seeing a post."

Jami Westervelt | City of Gustine

Different methods should be used to invite and encourage residents to participate. Examples include:

- Partnering with community leaders, organizations, health agencies and "promotoras" to assist with outreach as they have relationships with existing networks of residents who may be more likely to respond to invitations from that particular organization.

- Identifying a neighborhood youth or a respected adult resident who can be asked to assist or lead the outreach process. An example of a resident becoming a community leader can be found on page 54.

- Conducting door-to-door in-person meeting invitations. Some SPP applicants reported that in-person invitations inspired residents to participate. Making it clear why their input is needed, and how accessible the meeting is, may increase attendance.

- Providing incentives to increase turnout. One incentive may be to explain how the meeting will be an interactive park design process. Or, a local restaurant or business may donate food or prizes to help attract residents, while promoting their own business and roles in the community. Make the incentives clear in the invitations.

- Developing invitations and meeting materials in commonly spoken languages. These materials are often helpful and welcoming. All invitations and meeting materials should clearly state if language translators will be present at meetings. SPP applicants have had success in finding residents or local students to serve as volunteer translators.

- Providing invitations that are clearly welcoming to multiple generations. Local agencies reported that parents often assume children are not welcome to local government planning meetings. Help participants understand how the meeting will be interactive for all ages and when the meeting will start and end.

- Mailing flyers to residences within the half-mile radius. Surveys may be included.

- Collaborating with local schools to schedule meetings with health, physical education, or art classes. Schools can also send notices through an online portal or use flyers to inform milies and youth about when and where upcoming park design meetings will take place.

- Posting flyers in high foot traffic areas such as bus stops, major intersections, stores, schools, community centers, faith-based institutions, and libraries. Place flyers on the windshields of vehicles in parking lots.

- Using social media, local radio, television public service announcements, or local newspapers to distribute information.

- Scheduling one or more meetings where residents will already be present. For example, meeting with youth at a school, seniors at a center, or parents at a PTA meeting may not get you a Broad Representation in each meeting. However, the cumulative effect of the separate meetings may result in a Broad Representation of Residents.

"A favorite planned engagement activity was our city preschool students partaking in a "Design Your Park" activity with our Perris Senior Center members. Each student was paired with a senior member to draw and design their park. Perris seniors really enjoyed this activity, and have since requested staff to plan more activities of the type. Not even the language barrier amongst a few impeded the success of this activity; it was priceless to witness!"

Richard Belmudez | City Manager, Perris

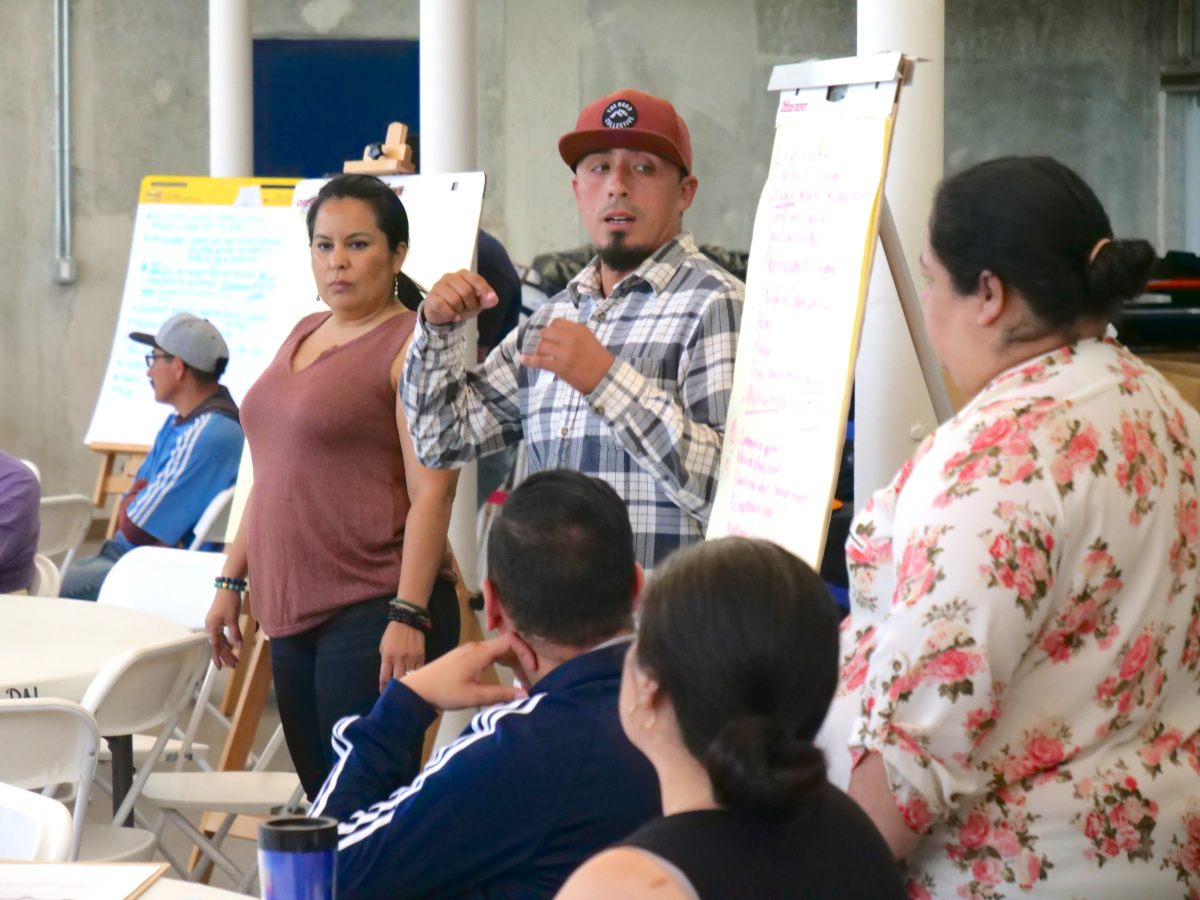

3. Conducting Five Meetings to Achieve Three Park Design Goals

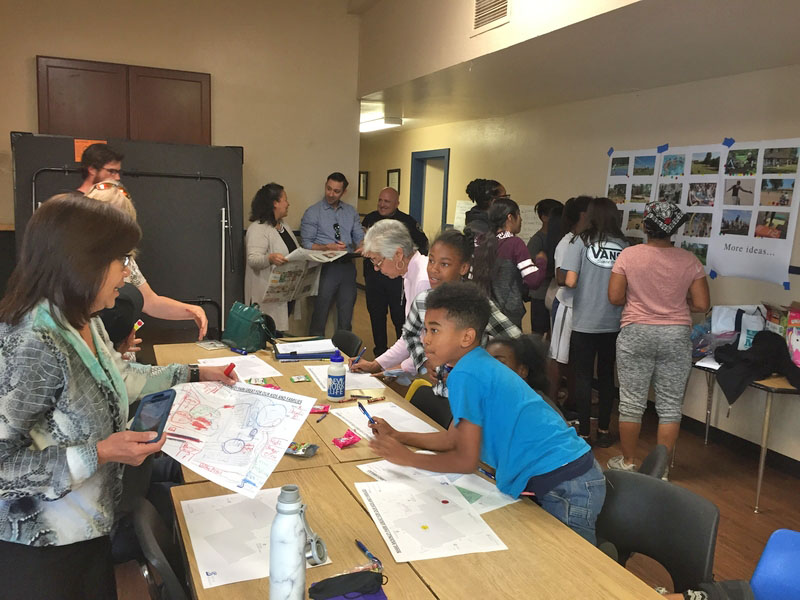

This final step involves strategizing how to encourage a group dynamic during park design meetings where participants can build upon the ideas of one another.

Engaging in interactive group discussions can lead to a more in-depth understanding of what the residents need, and also allow for detailed design ideas to enhance the park's use. SPP encourages three park design goals for the meetings. These three goals offer a blueprint for a popular, functional, beautiful, and safe park of which all generations of residents may enjoy. This section provides detailed guidance about how to achieve the park design goals during the meetings.

The three park design goals to achieve during the meetings are:

Park Design Goal 1: Selection and design of the recreation features.

Park Design Goal 2: Location of the selected features within the park.

Park Design Goal 3: Safe public use and park beautification.

"As Recreation Professionals, we often have a general idea as to what our community wants and needs in our neighborhood parks; however, Community-Based Planning allows for a much deeper connection to the neighborhood and ultimately leads to a much better project with much more community pride.

It brought the whole neighborhood closer together."

Tina Cherry | Community Services Director, City of Monrovia, Lucinda Garcia Park pictured above.

The following three pages provide specific ideas for park design goals, the following three pages provide general ideas about conducting thoughtful and productive community engagement meetings.

- Plan a Meeting Agenda: Plan how the meeting will be conducted. Consider activities, materials, times for each activity, ground rules, who will lead the meetings. And, most importantly, who will take notes to capture ideas for the three park design goals.

- Help Prepare the Residents: Consider having a welcome table with printed agendas that explain the reason for the meeting and each activity.

At the start of a meeting, explain the three park design goals. Explain why ideas are important. Meeting ground rules should encourage participation.

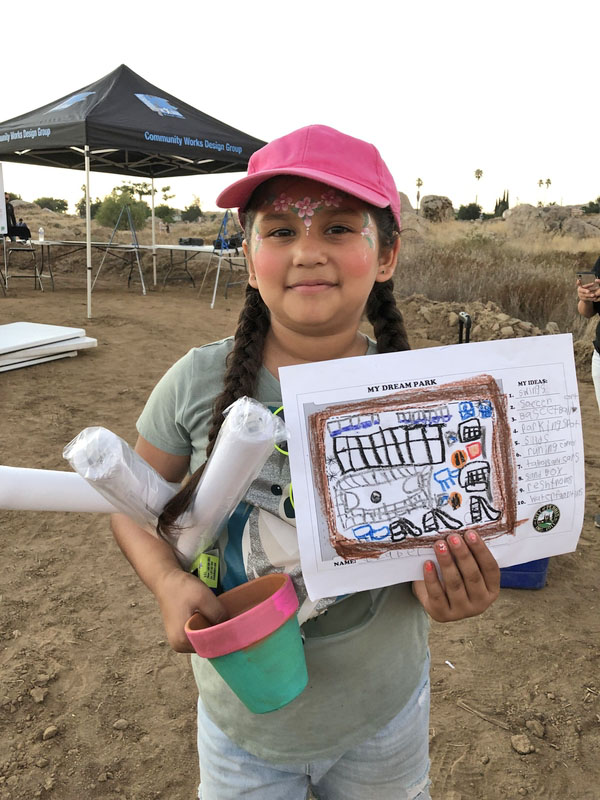

If there are subsequent meetings, provide a schedule with their time and place. - Enthusiastically ask for ideas: When a group initially has few ideas, the facilitator may need to give extra encouragement for residents to speak up by explaining why their ideas are important for a successful park design. Some residents may not be comfortable speaking in groups. Having paper and colored markers for noting or drawing ideas is another way to encourage participation. Plan how to manage when a resident goes off topic or has impractical ideas. Solutions include taking down the resident's idea and moving on, or suggesting how the topic can be addressed at another time, or reminding the participant what the task is. As residents feel more welcome to share ideas, some of the most feasible, practical, and previously unthought of ideas may come from unlikely sources. For example, engage children at the meetings by providing them with pictures, stickers, and art materials or other tools to articulate ideas. Some children may be enthusiastic and willing to add to group discussions. SPP projects have incorporated creative design ideas from children.

- Open Communication: View this as a partnership between the professional knowledge of the applicant or partner's staff, combined with the knowledge of the residents who live in the community.

Starting meetings on a positive note encourages a creative brainstorming process; and, if a popular idea emerges, but is not feasible, explain why. Be transparent about budget, regulations, long term maintenance costs, or other constraints. Open communication between professional park designers and neighborhood residents is a key for maintaining a balanced partnership. For example, the community may request an aquatic center but the grant applicant cannot commit to the long-term funding needed to operate and maintain it.

If the meetings are part of a competitive grant program such as SPP, make it clear to residents that in these types of statewide programs, more funding is usually requested than what is available. Be prepared to discuss other options if the project is not selected for funding by the state. - Residents may become meeting leaders: Look for residents who appear enthusiastic and are willing to take on a leadership role. These leaders can assist with facilitation and may also serve as volunteer translators.

There have been examples where a resident's talent was discovered, and they became professional community-based planners! - Tracking Ideas, Voting, and Confirming the Results: Tracking the ideas from each meeting is essential. Residents need to know that their ideas are valued and their voices are being heard. Examples of how this can be achieved include:

- Reviewing the list of residents' ideas, at the end of a meeting, confirms understanding of ideas that rose to the top. This may involve holding a vote to achieve consensus. Include this recap of residents' ideas in the Agenda plans.

- Sharing with new participants what was learned from prior meeting(s). Revisit ideas, ask for improvements, or even alternatives, to help continue to shape the park design in each subsequent meeting.

- Explaining what will happen after the meeting. If more meetings are planned, provide a schedule or website/social media to track the project.

Here's a brief summary example from a SPP applicant about how they achieved three design goals in one meeting.

"While partnering with the Soledad Youth Leadership Group and providing a translator at meetings, we used creative methods such as:

- For Recreation Features: We started with 'Design a Park' handouts to brainstorm, draw, and share park ideas for recreation features and design details.

- For Location of Recreation Features: Residents worked in groups (viewing the site as a puzzle activity) to recommend the placement of features.

- For Safety and Beautification: With a 'Safe and Beautiful' handout, the residents ranked their favorite safety and beautification ideas.

Then, in groups, they discussed their choices and embellished conceptual plans with their ideas."

Linda Palmquist | MNS Engineers

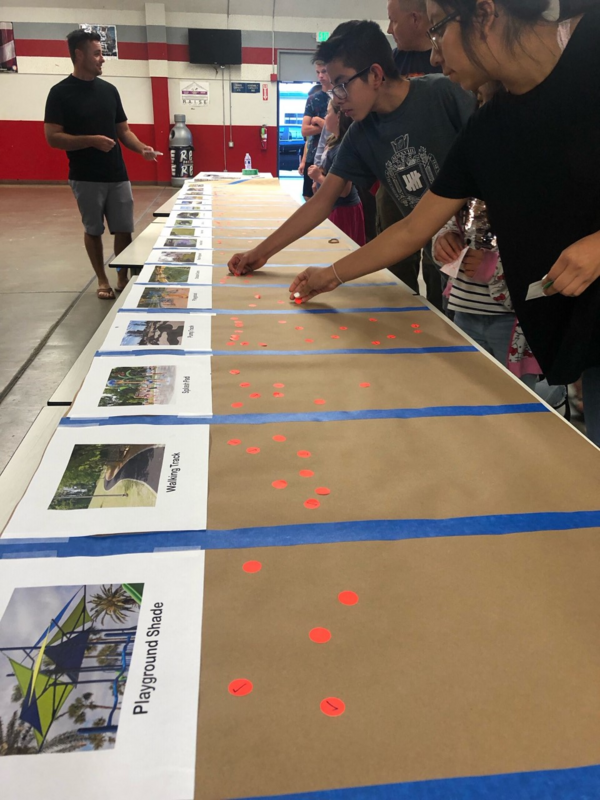

Park Design Goal 1 - Selection of the Recreation Features

From the SPP Application Guide:

"Describe how the Residents were enabled to identify, prioritize, and then select recreation feature(s) for the proposed project. The goal is to ask Residents what facilities they want in the park."

Identify: How will the meeting allow for creative brainstorming of recreation features? Will they start with a blank slate or a list of features to choose from? Will residents be given the opportunity to add recreation features to a list?

Prioritize: Once a list of recreation features is created, how will they be prioritized? For example, will a voting system be used, and how will it be managed?

Select: How will the process of identifying and prioritizing recreation features result in the project's final scope?

Examples of Goal 1 - Selecting Recreation Features During Design Meetings

Methods to select recreation features include:

- Residents can brainstorm to create a list. To energize participation, prompts can include instruction to residents on, for example, considering how designs can support healthy activities and social wellness for all age groups. Some applicants have used photos of features as prompts to spark ideas. If photos are used it is important to encourage residents to think beyond those provided. Photo prompts should be utilized to stimulate conversation and not as a listing of available amenity listings.

- Blank maps of the project site where residents note or draw the features they want and their locations. Their suggestions can be translated into a list of ideas.

- An interactive voting system with stickers placed next to features enables participants to view communal priorities in real time.

- A price system (participatory budgeting) can be helpful. For example, residents are asked to prioritize $50 (representing $5 million) in features, by choosing from a list of features assigned representative costs totaling $200.

Generally, grant applicants and the general public will want to know the range of possible recreation features available. The following list, created from statewide feedback, illustrates an extensive range of community park features. The list is in alphabetical order and is not intended to show a preference from top to bottom. Please be aware that there may be other recreation features that can be included beyond this list.

- Amphitheater/performing arts dance, music, and theater stage.

- Athletic fields (soccer regulation size or "futbol-rapido," baseball/softball, football).

- Athletic courts (basketball, "futsal," tennis, pickleball).

- Community gardens, botanical orchards demonstration gardens and orchards.

- Community/Recreation center.

- Dog park.

- Running track/walking loop, par course.

- Non-motorized trail, pedestrian/bicycle bridge, greenbelt/linear.

- Outdoor gym exercise equipment.

- Open space and natural area for recreation.

- Picnic/Bar-B-Que areas.

- Playground and tot lot.

- Plaza, Zocalo, Gazebo.

- Public art (mosaic tiles, sculptures, murals).

- Skate park, skating rink, and BMX or pump track (non-motorized bike tracks).

- Swimming pool, splash pad, aquatic center, fishing pier or paddling launch site.

- Lighting to allow for extended nighttime use of a recreation feature.

- Shade structure/covered park areas over a recreation feature to allow for extended day time use.

"In all communities engaged, what seemed to resonate with people was that they had a blank slate to work with...hearing them and taking to heart what they wanted to see in their parks."

Bill Jones | Chief Management Analyst, City of Los Angeles, Department of Recreation and Parks.

"The Sycamore neighborhood gave enthusiasm, creativity, and support for designing their park. The Antioch Police Department, churches, and nonprofits stepped up. One of our best meetings was during drop-in summer camp. The kids talked and drew their pictures. When asked about the oval he drew, one boy said '…I need a path to ride my scooter!' It will happen." ,

Nancy Kaiser | Director, City of Antioch Parks & Rec

Park Design Goal 1 – Designing Recreation Features (Process)

After selecting the highest priority features for the park, it's time to gather design ideas for those features.

From the SPP Application Guide:

"Describe how the Residents were enabled to provide design ideas for the selected recreation feature(s). The goal is to ask Residents for detailed design ideas of the features, after the features are selected."

Ask for detailed design ideas to enhance a recreation feature's function, materials, themes, color, size, shape, etc. Methods may include:

- Use photos as a starting point.

- Provide paper and pens for residents to sketch ideas.

- Create a brainstorming list and then gather feedback or vote on favorite ideas.

- Remember, not all recreation features are built alike. The design details can enhance the use and quality of a recreational feature.

Design detail examples of play areas, basketball courts, and soccer fields are shown on the following pages.

Park Design Goal 1 – List of Design Ideas for the Recreation Features (Outcome)

Finalizing a list of design ideas for the recreation features completes the step above.

From the SPP Application Guide:

"List the residents' ideas that will be included in the design of the recreation feature(s). Avoid listing ideas that will not be included."

Throughout the meetings, maintaining a list of accepted design ideas for the recreation features is helpful. Eventually, the list will be incorporated in bid packages and construction documents. For this reason, only the final accepted ideas should be on the list. The list for the design of the selected recreation features should represent detailed design ideas, such as function, materials, theme, color, size, shape, and number.

Examples of design details can be found on the next three pages.

Examples of Design Details

Are All Playgrounds Alike?

These are examples of different playground "design details" that enrich park use.

Are All Basketball Courts Alike?

Full vs half court, backboard, goal standards, surfacing are examples of different court "design details."

Are All Soccer Fields Alike?

For athletes, coaches, spectators, these are "design details." Surfacing, space, netting, fencing, lighting, sun orientation, and safety ideas are important when designing sports fields, courts, and other features.

Park Design Goal 2 – Process to ask for Ideas about the Location of Recreation Feature(s) Within the Park.

From the SPP Application Guide:

Describe the process that enabled the residents to express their preferences for the location of the recreation feature(s) within the park."

- Get different ideas about the layout of the park's recreation features for both practical function and safety reasons. Consider which features should be closer or further away from parking or busy streets, which areas of the park can be active (louder) or passive (quieter), scenic viewing areas, how fields/courts are oriented towards the sun for sports events.

- Residents will often have practical ideas about locating features, including enhancing park safety. For example, a parent may suggest locating playgrounds further away from streets or closer to field bleachers.

- Think of it as drafting the future site plan. Use an aerial image of the site and give residents cut-out figures that represent the size and type of selected recreation features.

- At project sites, some applicants have set up temporary markers to give residents a feel for the "footprint" of park features. This allows participants to visually test and provide feedback on the proposed spatial orientation of the features.

- Choose a method that makes the most sense for your available resources.

Park Design Goal 2 – List of Reasons for Locating the Recreation Feature(s) within the park.

Finalizing a list of locations for the recreation features completes the step above.

From the SPP Application Guide:

"List the reasons that will be used for the location of the recreation feature(s) within the park. Avoid listing reasons that will not be used."

Throughout the meetings, maintaining a list of accepted ideas for the location of recreation features within the park is helpful. Eventually, the list must be incorporated in bid packages and construction documents. For this reason, only the final accepted ideas should be on the list.

For the new fully accessible Empowerment Park, the Sacramento Parks Foundation and O'Dell Engineering set up temporary features to test the layout of the park.

"The engagement process...brought a level of energy...that helped uplift the effort. The interactive nature of the drop-in meeting produced good feedback."

- Sacramento Parks Foundation

Park Design Goal 3 – Process to ask for ideas about safe public use and park beautification

"The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system." Frederick Law Olmsted in 1848

From the SPP Application Guide:

"Describe the process that enabled Residents to provide park design ideas for safe public use and park beautification."

This third goal for the park's design seeks residents' ideas about safe public use and beautification. Both safety and beautification are critical to a park's success.

Safe public use: If residents do not feel safe, they will be less likely to use the park.

- Ask how the park design can incorporate safe public use. Consider lighting throughout the park or other things to assist police and minimize hiding areas for illegal activity.

- Once the general ideas of park safety are established, the discussion can move to specific features.

- Inviting the local police and fire departments to participate may help build connections and provide design insight for safe public use.

- Remember that neighbors who live near the project site often have first-hand knowledge of problems in the area and may also have suggestions to improve safe public use.

Park Beautification:

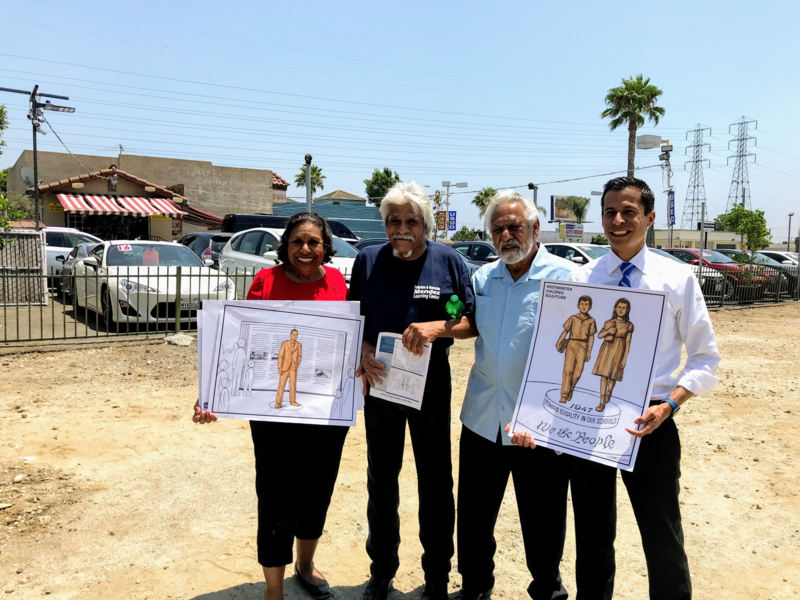

The community's physical environment and mental health of residents can be improved through a scenically pleasing park. This final design goal involves landscaping or public art.

Explain to residents that this goal is to make their park beautiful!

Art to beautify the park:

- This may involve public art themes that are important to the residents. Explain that art such as mosaics, tiles, murals, and sculptures can be developed to beautify the park.

- Residents may offer art concepts to capture the project site's history, or the community's cultural or natural history, or other recreation themes. Cultural conditions can be improved through public art in parks that reflect and celebrate the history and diverse cultures of surrounding neighborhoods.

- Examples seen in SPP projects included handprints by local neighborhood children added to wall tiles or pathways, tiles created by a nearby school's art class, murals to beautify a structure, or sculpture. A school art class and artists can suggest design, placement, installation, and maintenance.

Landscaping to beautify the park:

- For landscaping ideas, photos of trees and plants can help start the discussion.

- SPP encourages the use of native, drought-tolerant plants, trees, and flowers to create a "sense of place" in the park.

- Urban farms, fruit, vegetable, and herb gardens can add beauty while celebrating the residents' culture. These gardens can bring together all ages to learn about their own and other's heritage.

- Gardens can also provide an area for quiet reflection.

Examples of park beautification are below.

Park Design Goal 3 – Create a list of safe public use ideas that will be included in the project

From the SPP Application Guide:

"List the Residents' (safe public use) ideas that will be included in the proposed project. Avoid listing ideas that will not be included."

Throughout the meetings, maintaining a list of accepted design ideas for safe public use is helpful. Eventually, the list will be incorporated in bid packages and construction documents. For this reason, only the final accepted ideas should be in the list.

"I think the most significant benefit (and somewhat unexpected as well) is that the community engagement process truly did result in a better park design for both the community and the County! The community came up with ideas beyond what Parks and Recreation staff had discussed. Community ideas allowed the project to progress and garner wide-range support. For instance, one of the neighbors near Walnut Park was very concerned about the park going in next to her mother's home. She was actively against the projectvinitially, but as she joined one of the groups at a community engagement event and began to discuss her concerns, she changed her mind on the project. She alone came up with the idea of having a sheriff's office on the site to help with possible crime and vandalism. That idea was adopted by all the groups. It was her input that helped create a better park design and a better 'fit' in the neighborhood by addressing ongoing neighborhood concerns. In the end, she was one of the biggest proponents of the project."

Todd Schmit | Section Head for Landscape Architecture and Design, Planning and Development Agency, County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation.

Park Design Goal 3 – List of park beautification ideas that will be included in the project

From the SPP Application Guide:

"List the Residents' (park beautification) ideas that will be included in the proposed project. Avoid listing ideas that will not be included."

Based on asking for park beautification ideas, this is the "outcome" of the process.

Throughout the meetings, maintaining a list of accepted design ideas for park beautification is helpful. Eventually, the list will be incorporated in bid packages and construction documents. For this reason, only the final accepted ideas should be on the list.

Art examples for park beautification:

"Placemaking" is an interactive community-based planning technique where park beautification art celebrates a sense of place.

"Growing up in Westminster my whole life, I never heard about Mendez v. Westminster until I was in college. This park will mark the City of Westminster's place as one of the birthplaces of civil rights."

Councilmember Sergio Contreras

"India Basin (900 Innes Boatyard) is the most ambitious park project in a generation, and we wanted to design something not just for the surrounding community, but with them. It's going to be an anchor of health, safety, economic development, culture and environmental justice in the neighborhood. We are so proud to be working alongside them to make it happen."

Phil Ginsburg | General Manager, San Francisco Recreation and Parks

"The most significant unexpected benefit of the community engagement process has been the unique opportunity to envision a park plan that celebrates our diversity while honoring Black history. We have opened a conversation with our community that has empowered their voices. Together we are building a beautiful park for the future designed by the residents that live here now. It will be a joyous occasion to see the results."

Jackie Flin | Executive Director, A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI)

Park entrances which celebrate the community's identity while beautifying the park.

"We will be able to honor a fallen soldier, Tyrone Edward Carney, who was the first African American from Sobrante Park to die in Vietnam 51 years ago. The park will also provide a much-needed space of healing and peacefulness for residents of all backgrounds."

Cynthia Arrington | Community leader and president of the Sobrante Park Neighborhood Crime Prevention Council and Resident Action Council

"For 40 years my mother, then I, tried to have this lot full of weeds cared for. It was rodent-infested and developers dumped here late at night. Everybody is excited waiting for the grand opening. We all fought for this. It brings me a lot of joy seeing the community look out for this park at all times of night while it's being built."

Ronald "Kartoon" Antwine

In summary, the framework of the steps learned through SPP are:

1. Schedule Five Accessible Meeting Locations and Times

2. Invite a Broad Representation of Residents

3. Conduct Five Meetings to Achieve Three Park Design Goals

Park Design Goal 1 - Selection and design of recreation features.

Park Design Goal 2 - Location of selected recreation features.

Park Design Goal 3 - Safe public use and park beautification ideas.

4. Documenting the Outcome

As the project moves from community-based planning to the preparation of construction documents, other employees or contractors may take over the project.

This often happens when construction documents are being prepared, or the project goes "out to bid" for construction. The accepted ideas, if not clearly documented, can "get lost in the shuffle" as the project moves forward between engineers and contractors. To avoid losing the ideas, go through the community-based planning process with the intent to present an outcome. A site plan drawing and descriptive list helps to clearly document the outcome!Site Plan Drawing: This is a "bird's eye view" of what would be built in the park.

- Identifies the features to be developed and their locations.

- A resident or art student/class can help draw it.

- Assigning numbers or symbols to a corresponding list increases clarity.

Descriptive List: This is a numbered list to help document the design details that a drawing does not explain. The list can correspond to the site plan by describing these design details.

- Selected Features per pages 31-34.

- Design details for those features per pages 35-36.

- Location of those features within the park, and reasons why, per pages 37-39.

- Safe public use per pages 37, 39.

- Beautification per pages 37-38, 40-46.

"Community-based planning allows the opportunity to give community members a voice and creates relationships that bring insight and perspectives that are normally ignored. Regardless if the grant is awarded, it is a worthwhile experience in future revitalization opportunities."

Francesca Sciamanna | Community Services, City of Bell

Building Social Capital, Cohesion, and Capacity

The SPP community-based planning process produces unexpected benefits. Conducting in-person meetings with a broad representation of residents creates a sense of place. By giving communities a voice in park design, there is a synergy that develops leading to building community capacity.

State Parks emphasized how park development projects improve the physical environment of communities. During conversations with Round 3 SPP applicants throughout California, an interesting and unexpected statewide pattern about this process began to emerge:

By designing a park, SPP community-based planning also builds "social capital!"

As defined by Oxford Dictionary, "Social Capital" means:

"The networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively."

Designing a park is a catalyst that brings residents, local agencies, and community organizations together to serve their community. When residents work together to transform an area into a vibrant park, it becomes a symbol of community pride.

The following pages provide quotes from communities about how this process strengthened relationships between local government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and neighborhood residents.

"Just planning the park has brought the community together. Boorman Park is the community's baby. This project reflects in-depth community planning to represent what we really want and need in a park. This grant gives us the inspiration to keep active in the community. We are so proud of this effort. The community has finally been heard and our kids will benefit for years!"

Maria Isabel Barrera | West County Regional Group member and resident of the Boorman Park area.

"Having the community deeply involved in the design is key. Because sometimes people see things that you don't. We had a team of people from the community to plan and do all the outreach themselves. That really worked. We had to work together, collaborate together, to figure out how to approach and bring in the whole community. That process of people from the community working together breaks down barriers, connects families, and builds trust."

Carmen Lee | Resident, Richmond's Pogo Park

"An unexpected and exciting benefit of the process was seeing new relationships and even friendships being created between diverse community members where none existed before as a result of them meeting each other at the community meetings. It made our meetings better and it made the community stronger."

Doug Pickard | Parks Project Specialist, City of Fullerton

"An unexpected benefit of the process was the community building - I liked meeting fellow neighbors and hearing their ideas."

Yanel Saenz | resident

"It was wonderful to see how much a person's attitude towards a project or amenity could change through the enthusiasm of other community members that they may rarely interact with. For example, a woman who came in staunchly against a skate park because she had preconceived notions about the type of person who would use the skate park became a supporter by listening to the members of the Skate Movement and what they were doing for youth in our community. Broadening horizons and understanding the wider needs of the community is awesome!"

Jennifer Moore | Recreation Supervisor, City of Redding

"A significant benefit is the number of people I met whom I've never had the pleasure of meeting….new park 'sparked' their interest."

Mikal Kirchner | Director, City of Selma Recreation & Community Services

"Many were happy to know their voices were being heard."

Noel Castillo | Public Works Director/City Engineer, City of Montclair

"I think it was great to see such a diverse group of community members come together with a common goal - improving community health and open space access for all. Everyone's goals are the same."

Gabriel Teran | City of Oxnard Parks, Recreation, and Community Services Commissioner, about Campus Park Planning

"Participants worked surprisingly well together as a group to develop a plan that would best benefit all. They took ownership of the project and interest in the process."

Jami Westervelt | City of Gustine

"The community engagement process cast a wide net in its scope and hearing what the seniors wanted for their recreation needs was a significant benefit."

Laura Fischer | General Manager, Heber Public Utility District

"Residents were encouraged to assume the role of landscape architects and design their ideal park for the community as a whole, integrating diverse themes and park elements that had been voiced. A significant benefit of the community engagement process was having diverse residents' ideas coalesce into a consensus approved design that integrated passive, active, and cultural elements. For example, Mixteco residents in need of a Pelota Mixteca court shared their needs, and everyone at the workshops supported their idea and integrated them into their preferred park designs."

Eric Humel | City of Oxnard

"One of the young people that I walked up to and asked them to do this survey turned out to be our committee leader. She has a natural leadership quality… I would also constantly refer to it as ‘their park'. That made them want to be there and put their heart into making this park something special...This park represents who they are and their heritage; it tells a story."

Sonia Hall

"The community leaders in the Airport neighborhood selected to make improvements to Oregon Park as a first step towards revitalizing this challenged neighborhood. The Airport Neighborhood Collaborative is composed of parent leaders, organizations, business leaders, non-profits, elected officials, city and county departments in the interest of supporting the neighborhood health, safety, and well-being."

Lourdes Perez | Program Manager, Cultiva La Salud

Finding Talent in Residents During the Community Planning Process

When residents are empowered to work together with local government or non-profit organizations, some may show a natural ability to inspire community-driven efforts. Enthusiastic and talented resident leaders discovered through the process have been recruited to join an organization's or agency's workforce. Here's an example!

"My name is Kimberly McCoy and I am from Fresno, California. In 2012, I was frustrated with local political decisions affecting my family. I was looking for a way to get involved in my community and volunteered. I received training on how to connect with other neighbors and be civically involved, which I enjoyed. I became a team leader and led door-to-door and phone banking campaigns throughout the Central Valley to connect everyday people to decision-making processes and help them understand how to engage in issues they care about. In 2014, I was promoted to a community organizer. I conducted one-on-one visits and led house meetings with residents in communities that wanted to create change.

I learned about the importance of:

- Empowering people by removing barriers that often prevent them from engaging civically – from scheduling meetings during community-friendly hours to ensuring that interpreter and childcare services are available.

- Identifying community strengths and assets and building on those.

- The power of relationships. Social capital is one of the most overlooked assets in many communities. In order to be successful on any issue or campaign, relationships must be nurtured, and people must feel like they are active decision makers. That is why I begin by meeting people where they live to understand what issues are important to them.

In 2018, I was hired as Project Director for Fresno Building Healthy Communities and led signature gathering efforts to advance local measures such as Measure P on the November 2018 ballot for parks, arts, and trails in the City of Fresno. I continue to support community groups in identifying, planning, and implementing strategies to advance a common agenda of community health. In 2019, I was selected to be a voice for the community on the AB 617 Community Air Protection Program Steering Committee, to elevate community priorities and emission reduction opportunities in Fresno's most impacted communities.

I have enjoyed being able to connect and build relationships with residents, shaping decision-making processes and supporting my neighbors to leverage their power by using their voice. That is how we will continue to build healthy communities with authentic community engagement. I hope my story can inspire other residents to become a leader for their community. Thank you."

Kimberly McCoy | Project Director, Fresno Building Healthy Communities

Future Planning Efforts

Encouraging community-based planning in grant programs is founded on this basic question: For community parks, should the state prioritize one type of recreation facility over another, based on national, state, or regional surveys?

Historically, in competitive programs, grant writers and even grant guidelines cited national, state, or regional surveys to determine what types of recreation facilities should be in a community park. For example, the results of regional or statewide surveys were used to prioritize which type of facility ranked higher in California's competitive Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) applications. A picnic area ranked higher than a playground, a baseball field ranked higher than a soccer field, and a tennis court higher than a basketball court.

During application workshops of prior grant programs, however, local government applicants frequently reported that their community's needs were different from the statewide or regional survey results. National, state, or regional surveys may not capture the priorities of cities, and even more specifically, of neighborhoods within different areas of the same cities. Community parks provide close-to-home park access, particularly for seniors and children. Each community has unique unmet recreation needs for park access and infrastructure.

For these reasons, SPP prioritizes new park access while encouraging flexibility in park design responsive to each community's unique recreation needs. Due to the recent 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, new community-based planning methods following health guidelines will be tested for the next round of SPP grant funding. To inform future planning efforts over the next five years, State Parks' CED will continue to share successful methods learned through the SPP model.

Please find both inspiration and confidence to use this model.

By doing so, you will design a vibrant park reflecting the community's unique needs and identity. Further, it fosters an added benefit by bringing together neighbors, local government, and community organizations. Using the SPP model builds social capital when participants realize their common goals.

Engaging neighbors to plan a park for all to use can be a life-changing experience.

Enjoy the journey!

Parks are unique places where children can play, families and friends bond, people exercise, seniors socialize, youth are mentored, cultures are celebrated, and everyone connects with nature. For these reasons and more, vibrant parks funded by the Statewide Park Program create healthier communities.